This article is part of a series on American history. Cross-reference to chapters 12-13 of A Patriot’s History of the United States and chapters 12-14 of A People’s History of the United States.

The average Americans, according to Patriot’s, had achieved prosperity unheard of in Europe, with a per capita income 25% and 40% higher than their British and French counterparts, respectively. The standard of living that this could buy was enough to impress visitors like Leon Trotsky, who marveled at the modern conveniences available in the “workers’ district” for only $18/month. Social activists “created entirely new subjects” in the social sciences for the purpose of claiming “superior understanding.” Patriot’s accuses progressives of “appropriating the concept of professionalism” and adopting technocratic language “despite the fact that Darwin, Marx, or Freud had never proven [emphasis mine] anything scientifically.”

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the progressive movement in America gained strong appeal in both political parties. For People’s, there is a clear explanation: “The Progressive movement…seemed to understand it was fending off socialism.” To Zinn, therefore, the progressive movement was a counterattack against socialism—while Patriot’s criticizes the progressive impulse as a beachhead from which socialism could eventually emerge.

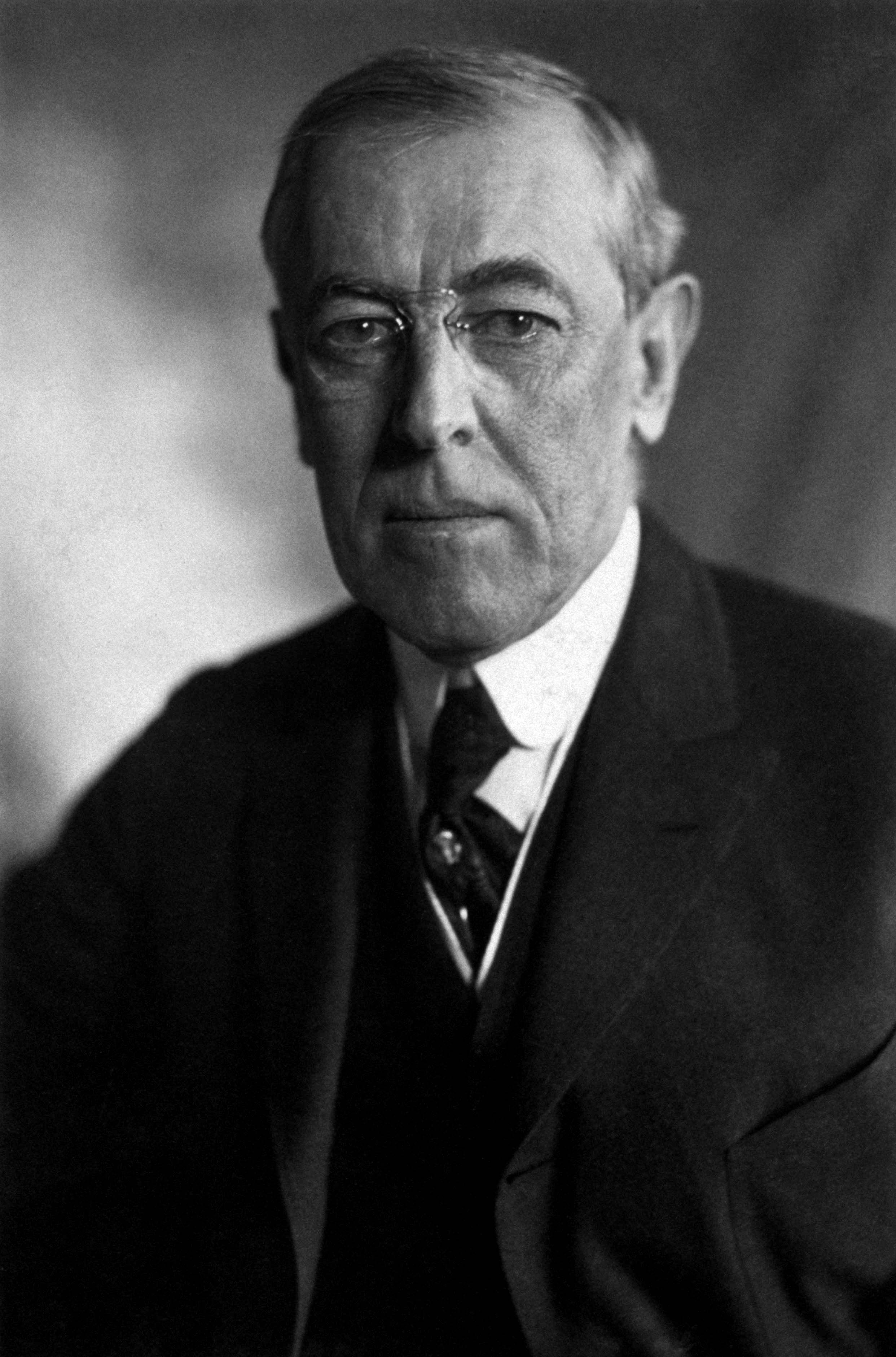

The progressive ideal came into its own just as world events created an opportune moment for America to take a major role in world events: relieving hapless Spain of many of her colonial possessions, and then boldly seeking to dictate terms to the war-torn nations of Europe. While much of president Woodrow Wilson’s vision fell by the wayside at Versailles, it represented an America willing and capable to take the stage with the greatest nations in the world.

McKinley: A “Principled” “Imperialist”

William McKinley won the critical 1896 election against William Jennings Bryan’s Democrat/Populist coalition. It was a close and contention election, one which solidified a Republican block that had existed since the Civil War. Between 1860 and 1928, only one Democrat—Cleveland in 1884 and 1892—would win a presidential election against a united Republican front.

As Patriot’s puts it, foreign affairs “crept into the spotlight” during McKinley’s term. The queen of Hawaii, Liliuokalani, sought to repudiate an 1887 constitution that granted foreign residents the right to vote, prompting a rebellion in 1893 that threw the island into turmoil. Since Cleveland’s administration, the government had treated this rebellion as a plot of Americans on the island rather than a genuine revolution. Hawaiian monarchs had entreated for annexation since 1851, when the U.S. Secretary of State politely declined. By the time McKinley was in office, a more assertive Empire of Japan had started encouraging immigration to Hawaii, and regularly sent warships there. Thus, to avoid a forward Japanese base in the Pacific, McKinley signed the annexation resolution in 1898. Had McKinley remained passive and allowed Japan to assert herself over the islands, it’s conceivable that the attack on the American Navy at Pearl Harbor likely would have come along the continental west coast, perhaps at San Francisco, and placed America at a greater disadvantage during World War II.

America was not new to interventions in its own hemisphere. People’s cites a State Department list of 103 interventions abroad between 1798 and 1895. In 1895, the people of Cuba revolted against the 160,000 Spanish soldiers that enforced the colonial regime. The new “yellow press”, named for the color of its paper, published sensational accounts of Spanish atrocities that both our authors claim contributed to American outrage. But it certainly helped that the Spanish minister to Washington wrote editorials lambasting president McKinley, and that an American battleship, the Maine, exploded in Havana harbor under then-dubious circumstances. American declared war in April, 1898.

As with the Mexican-American War, Europeans “again overestimated the decrepit Spanish empire’s strengths”. The Americans made quick work of the Spanish in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, crushing the Spanish navy with superior technology. Cuban and Filipino partisans played a critical role in the American victory, but the Americans occupied both territories, something People’s highlights and condemns, along with the brutal suppression of Filipinos who resisted the Americans. Patriot’s highlights the Teller Amendment, which committed the U.S. to withdrawing from Cuba within a few years, although this eventually came with some strings attached.

On the Philippines, McKinley checked his idealism. He considered the locals unfit for self-government (a point with which Tocqueville likely would have agreed), and knew that to abandon the islands was tantamount to inviting British or German occupation instead. So the Americans stayed, rejecting the independence-protectorate solution that the Filipinos favored. The Filipinos continued fighting for immediate independence until 1903. However, William Howard Taft proved a capable governor, producing “reasonable, concrete steps to reduce opposition.”

Ever critical of engagements in the name of capitalism, People’s cites two reasons for this expansionist bender: naval force projection as advocated by military theorist A.T. Mahan, and the need of a “foreign market” for American products. Just as Zinn criticized protectionist trade policies for furthering business interests at the expense of the consumer, he criticizes the impulse for free trade that blossomed once America became a nation of dominant producers. I would expect his explanation to be that any policy disproportionately favoring the business interests—regardless of what it is—is bound to be exploitative. This, alas, would be but ideology.

Teddy & Taft

McKinley won re-election in 1900, but was assassinated soon after by an anarchist. The presidency fell to Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, son of an old-money New York family, who exemplified the aggressive can-do attitude of the progressive age. He wrote a dozen books, lived on a ranch in North Dakota, and led a charge of American troops in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. He embraced the progressive idea of activist government, and brought into office an “antipathy toward corporations”, which Patriot’s suggests was rooted in an envy of the “new-money” men like Carnegie and Rockefeller, who had worked their way up from nothing.

Roosevelt applied his progressive furor to “trust-busting”—that is, bringing enforcement to the Sherman Antitrust Act that had lain dormant for nearly a decade. He brought suits even against business combinations that did not constitute a direct “restraint of trade”, but only the “threat” thereof. Patriot’s further cites research that suggests antitrust enforcements tended to harm the profits of all businesses—even the small ones whom the law was intended to protect.

Teddy claimed: “We don’t wish to destroy corporations, but we do wish to make them subserve the public good.” Patriot’s takes issue with this position:

Implied in Roosevelt’s comment was the astonishing view that corporations do not serve the public good on their own-that they must be made to—and that furnishing jobs, paying taxes, and creating new wealth did not constitute a sufficient public benefit.

This dynamo of a president continued American intervention abroad, essentially condoning a contrived revolution for Panama to break away from Colombia and become independent, enabling the Panama Canal to proceed—the French had started work on the canal in the 1870s.

Seeking to avoid a power-hungry image, Roosevelt chose not to run in 1908, instead selecting William Howard Taft as his successor. Taft, who truly wanted to be a Supreme Court Justice (and eventually became one) continued Roosevelt’s trust-busting policies. He also fought for a lower tariff, expending significant political capital and depriving the government of a key source of revenue. Eventually, he fell afoul of Roosevelt by making enemies of Roosevelt’s friends within his own administration.

“The Socialist Challenge”

Thus People’s describes the concerted efforts by the Socialist Party to gain traction in the United States. We’ve already seen Zinn’s description of progressive policies as a sop to prevent further Socialist gains, but a few key factors are worth highlighting.

Socialism founds its way into America through the unions. Some unions, like the AFL, remained politically agnostic, but others made no secret of their militant commitment to Marxism. Among these were the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). People’s mentions that the group never had more than a few thousand members at a time, with perhaps 100,000 total members coming and going through the life of the movement. The IWW was founded in Chicago by “two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists”, as People’s tells it. Though few in number, the IWW members punched well above their weight, led by a core of disciplined revolutionaries.

A union-on-wheels, the IWW worked to enlist local labor wherever it went, bringing strikes and conflict with them. While People’s claims the IWW “did not believe in initiating violence”, a great deal of violence always followed. IWW agitators went to jail in hundreds, then in thousands, but the pattern persisted.

All this occurred simultaneously with tremendous gains for Socialism at the polls. The perennial Socialist candidate, Eugene Debs, won 400,000 presidential votes in 1908 and 900,000 in 1912. As the party gained just enough electoral success to claim respectability, it began to repudiate the revolutionary tactics of the IWW, removing IWW founder Bill Haywood from its Executive Committee for is advocacy of violence—although People’s admits that Debs’ own writings were “far more inflammatory.”

Wilson & Progressivism in Action

In 1912, Roosevelt failed to reclaim the reins of the Republican Party, with Taft securing the nomination. Rather than declaring defeat, Teddy formed a Progressive Party, which advocated for an income tax and generally moved to the left of the Republicans. Together, the Republicans and Progressives had enough votes to soundly beat the Democrats; divided, they ushered Democrat Woodrow Wilson into the White House.

Wilson came from an academic background, where he advocated a “’middle ground’ between individuals and socialism”, as Patriot’s explains. He was well-positioned to cash in on the progressive wave, benefiting “from ideas already percolating through the system.” Yet Wilson was responsible for making many of these law—including the creation of the Federal Reserve system of American central banking.

Progressives had long since suggested an income tax (and Patriot’s claims the idea was “long cherished by socialists”). One had been in place during the Civil War, a 3% tax on only the highest earners. In 1894, Congress passed a 2% tax, again only on high incomes, but the Supreme Court ruled income taxes unconstitutional. However, Patriot’s reiterates that western land sales and tariff proceeds were key sources of government funds. Land sales were dwindling as the frontier was settled, and tariffs carried “tremendous political baggage.” Thus a direct income tax was enabled through the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, with progressive rates and a 7% rate for the highest incomes. Patriot’s points to income taxes as a contributor to the “hidden growth of the federal government.”

The new president was an idealist above all else, which left him in no mood to recognize the recent military coup in Mexico—even though Taft’s administration had been prepared to recognize the new government. Wilson intervened, sending American ships to shell a Mexican port, and ultimately backing different insurgent groups, who turned against the U.S. once American supplies stopped coming. Rebel leader Pancho Villa raided American border towns, and Wilson ultimately sent the U.S. Army into Mexico to capture him—to no avail. Wilson ultimately recognized his blunders and agreed to an international commission to negotiate a settlement between the Mexican parties.

Conflagration in Europe, Equivocation at Home

The events leading up to the outbreak of World War I certainly deserve their own post, and are too convoluted to fully cover here. Suffice to say that within months of the war’s beginning in 1914, the Germans and their (far less competent) Austro-Hungarian allies had entrenched themselves in forward positions on two fronts: one deep within France, the other within the Russian Empire. Poison gas, artillery, and trench warfare ensured massive casualties on all sides. People’s claims it was an “imperialist war,” and claims such a view “seems moderate and hardly arguable.” Given the complex chain of alliances and competing territorial claims of European powers, Zinn has a good point.

Some Americans (like Roosevelt) demanded America condemn the German invasion of neutral Belgium—which Germany had done simply as a shortcut to Paris. Wilson sought to remain as aloof as possible from Europe. His neutral position helped him win a narrow election against a reunited Republican ticket in 1916.

As Patriot’s put it, there was only one problem with Wilson’s neutrality stance: “the Germans would not cooperate.” Lacking superiority at sea, the Germans opted for stealth, preying on British and American shipping, sinking a passenger ship, the Lusitania in 1915, with over 100 Americans (and some war materiel) on board. People’s is skeptical: “It was unrealistic to expect that the Germans should treat the United States as neutral in the war when the U.S. had been shipping great amounts of war materials to Germany’s enemies.” American commercial relations were stronger with Britain than with Germany—Germany herself was under British blockade—and perhaps it was inevitable that America would take the Allies’ side as a result. Yet German machinations went further with a telegram to Mexico seeking to create an alliance against the United States, offering essentially the whole American southwest in exchange.

This Zimmerman telegram caused outrage, and Congress gave Wilson the declaration of war he sought within three months. In ”grandiloquent terms”, Wilson aimed to redefine the struggle as “making the world safe for democracy.” In practical terms, it represented an abrupt about-face that mobilized America’s industrial power almost overnight.

Germany and her allies were already near collapse by the time the American troops arrived. A last-ditch German offensive failed to reach Paris, and the Americans joined the counterattack. By November 1918, the Central Powers sought an armistice, ending the war.

A year prior, Russia had endured two revolutions—a moderate republican one in February, and a radical communist one in October. Vladimir Lenin immediately called for peace with Germany on any terms. Patriot’s saw the Bolsheviks’ victory as a threat, yet one which was welcomed by many American intellectuals, with one American sympathizer blithely claiming: “The execution of dissidents sounds like democracy to me,” without a hint of irony. Yet with the Bolsheviks in power, American radicals sought to take initiative, with the Justice Department cracking down ruthlessly to “smash” the communists in the United States. Two anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, were convicted and executed in a controversial ruling—a ruling which Patriot’s says looks firmer with time, and which People’s insists was only because “they were anarchists and foreigners.”

As with most wars, People’s takes a critical stand, suggesting that “American capitalism needed international rivalry…to create an artificial community of interest between rich and poor.” This ignores the idea that business hates uncertainty more than anything else—and that war is the greatest uncertainty there can be.

Pontificating in Paris

Woodrow Wilson arrived to the peace talks well versed in his own idealism. He had issued the Fourteen Points, the Four Principles, and the Five Particulars regarding the postwar order, all of which he brought up before the fighting had stopped. Demanding a League of Nations, self-determination of peoples, and generally giving the Germans an easy peace, Wilson’s program was attractive to the Central Powers. The British and French, who had done most of the fighting and dying, ultimately insisted on a far more draconian peace. This left Germany feeling betrayed, since they had already agreed to Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and likely contributed to German feelings of injustice that fueled the rise of Hitler.

Patriot’s is no fan of the treaty either: Where the treaty was not self-contradictory, it was mean, vindictive, and, at the same time, ambiguous. Republican forces in the Senate demanded clarity on what “self-determination of peoples” meant—for instance, independence for Hispanics in the American southwest or French Canadians in Quebec? Suffering three strokes near the end of his presidency, Wilson failed to bring his idealistic vision of world relations into reality, and the Senate did not agree to commit America to the League of Nations.

Progressive Legacy

Many other achievements came from America’s progressive age. Women were granted the Constitution right to the ballot (individual states led the charge on this issue). Direct election of senators made Congress more responsive to the votes of the people, and took considerable power away from state governments. The income tax further solidified government power in Washington.

Prohibition, which Patriot’s suggest correlated strongly with universal suffrage, was the great overreach of the progressive age. Codified as a Constitutional Amendment, the Prohibition program failed due to poor oversight, generating a slew of corruption, illegal drinking, and organized crime that ultimately embarrassed the country.

On the darker side, many progressives embraced the science of eugenics—birth control advocates like Margaret Sanger held to a Malthusian view of world population. Sanger viewed birth control “as a means of ‘weeding out the unfit’”, as Patriot’s tells it. This dangerous idea takes the progressive notion of perfectible man to its extreme—and dovetails with the awful racist views that Hitler held in Germany.

Patriot’s calls progressivism a “dark bargain”:

Women could vote, but now they could not drink. They could start businesses, but could not expand those companies lest they fall prey to antitrust fervor. Likewise, men found that Progressive policies had freed them from the dominance of the state legislators when it came to electing their senators, but then they learned that the states lacked the power to insulate them from arbitrary action by the federal government.

In our next post, we’ll cover boom, bust, and another world war.