What is Presidential March Madness?

In 2019, I came across the idea of hosting “bracket nights”—creating a single-elimination bracket for any subject matter area and gathering with friends to debate each matchup until one champion remains. Topics could include great scientists, statesmen, foods, amusement park rides, pretty much anything. Alas, the pandemic would scuttle bracket nights, along with most all other social plans.

The idea has remained one that greatly intrigues me, and I’ve decided to apply it to former U.S. presidents in a series of posts, in the spirit of the annual March Madness basketball tournaments going on around this time. Here’s how it’ll work.

- I’ll seed all former U.S. presidents in a 44-man bracket, divided into 4 quadrants of 11 each. Note that I’m excluding current president Joe Biden, both to avoid recency bias and to avoid judging him on only a portion of his time in office.

- Seeding will be based on this historical survey from 2021. I’m not endorsing these rankings, but we need a place to start for seeding—upsets can always happen!

- The first four posts in this series will cover one quadrant each, through the round of 16.

- The final post will cover the eight quarterfinalists.

- Each quarter of the bracket will be named for the top-seeded president in that quarter:

- 1: Abraham Lincoln

- 2: George Washington

- 3: Franklin D. Roosevelt

- 4: Theodore Roosevelt

Of course, any exercise like this is highly dependent on what kind of criteria we use. For instance, our authors of Patriot’s and People’s would likely have very different outcomes if they participated. Because of this, I encourage my readers to think through how you would decide each matchup differently, and what criteria you’re implicitly using. And if you differ strongly with any of my conclusions, mention it in the comments.

Here are my criteria, up-front and defined. As always, there’s a tradeoff between thoroughness and clarity. There are seven criteria: whichever president in a single matchup has the better record in four or more will win the matchup.

- Foreign Policy & Crisis Management. This includes actions taken to win or avoid wars, as well as efforts in navigating/preventing emergencies both at home and abroad.

- Consistency with American Ideals & Constitution. This refers, not only to the Constitution itself, but America’s other founding documents (the Declaration and the Federalist Papers, for instance). Part of the executive’s function is to uphold the ideas America is founded on: consent of the governed, equality before the law, and limits of governmental and executive power.

- First Citizenship & Contributions Out of Office. A good president avoids personal misconduct and retains some level of moral legitimacy. Also, a president’s contributions to America (or humanity) either before or after their time in the White House will be considered here.

- Having & Articulating a Vision for America. Another two-part criteria. It is not sufficient to simply have a vision so much as convey one, both to colleagues in government and the American people.

- Contributions to Prosperity. On some level, this encapsulates Reagan’s challenge to Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election: “Are you better off now than four years ago?” Of course, many such factors of well-being are outside presidential control, but the well-being of citizens is an area that governments should be judged upon.

- Minimizing Externalities. Many government actions have long-reaching consequences that will outlive the president who oversees their first implementation. In this category, there are bonus points for leaving the country “better than you found it”, and penalties for leaving a successor stuck holding a ticking time bomb.

- Vice President/Cabinet. I think it’s fitting that in the event of a 3-3 tie in the other six points, the quality of a president’s VP and cabinet should decide the matter. Especially as the executive branch has grown, it’s critical for presidents to surround themselves with conscientious and competent people.

One more procedural note: the numbers next to each president’s name refer to their rankings in the C-Span survey, not their chronological order.

With no further ado—let’s jump into the Madness!

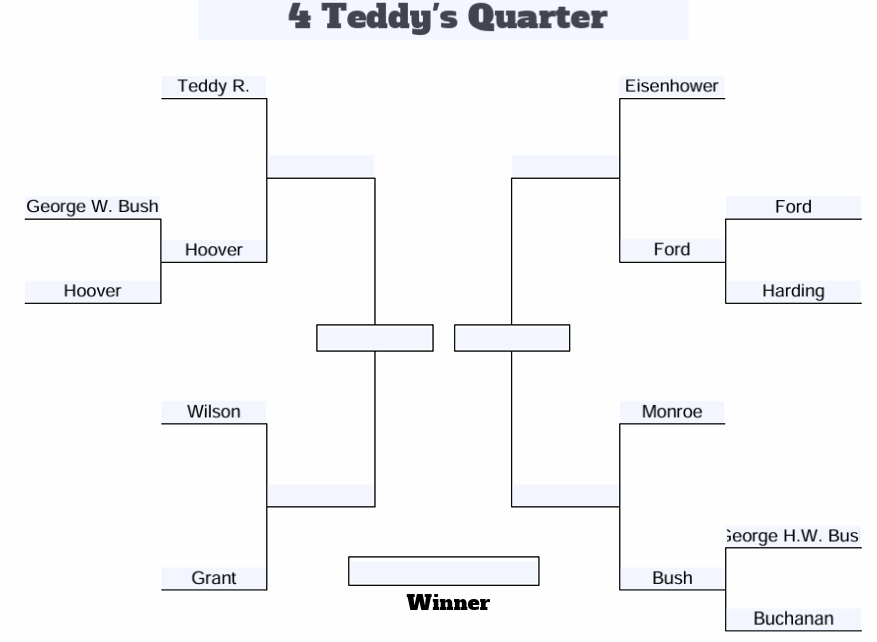

Teddy’s Quarter—Play-In Round

(29) George W. Bush vs. (36) Herbert Hoover

Hoover is often maligned for the Great Depression. I think many of the common criticisms go beyond the point of fairness. (One of the best presidential biographies I’ve ever read was this one of Hoover, which gives a far more comprehensive portrait of his career.) Whether or not this goes beyond the point of fairness, many of his policies did little to help—and his response was uninspiring. FDR was able to provide far more hope than Hoover.

Bush the Younger has a mixed record. He presided over a stronger economy than Hoover by far, despite the Internet stock bubble of the early 2000s. He performed better in the great crisis of his presidency (9/11) than did Hoover during the Depression. But I have to penalize him for consistency on laws like the Patriot Act. Regardless of whether this is sound policy or not, one does not need to guess what America’s founders would have thought of it.

Hoover gets the point for contributions out of office. Hoover led international efforts to feed civilians in occupied Belgium during World War I, and in many ways has the strongest humanitarian bona fides (out of office) of any president. I also give Hoover the point for minimizing externalities. This one is more controversial given the stinking economy that Hoover handed over to FDR. But Obama’s first term (following Bush) was marked by the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis, which began at the end of Bush’s time in office. Instead of weighing economic disasters against each other, I take as a tiebreaker some of the actions of overreach abroad (Iraq, for instance) that Bush also left for Obama to try and clean up.

At a 3-3 tie, we examine the cabinets. Neither appears to be significantly more capable than the other. I end up giving Hoover the point purely on the basis of their respective vice presidents. Dick Cheney (Bush’s) is considered among the most powerful VPs in American history. This isn’t a shot at Cheney’s policy recommendations, but simply my estimate that the Constitutional intention for the vice president was to play a far more limited and passive role. Because of this, Hoover’s relatively unobtrusive running mate (Charles Curtis, who was also the first VP of American Indian descent) gets the point, and hands the matchup to Hoover,

Final result: Hoover wins, 4-3.

(28) Gerald Ford vs. (37) Warren Harding

Ford has some weaknesses here, but it is still a mismatch. Harding’s scandal-ridden administration is no match. On scandals like Teapot Dome, Harding loses points for citizenship and cabinet. Ford also seals points on crisis management by his actions to put the Watergate nightmare of Nixon out of the nation’s mind. Succeeding to office following Nixon’s resignation, Ford pardoned Nixon (but not Nixon’s associates).

One’s opinions on such action beg the complicated question: do governments have better things to do than exhaust the public’s attention investigating prior governments? I have mixed thoughts here, but better to move on—in the end, Harding gets credit only for a generally sound economy relative to the inflation on the 1970s. Ford will have to wait for a true test.

Final result: Ford wins, 6-1.

(21) George H.W. Bush vs. (44) James Buchanan

Someone had to be at the bottom of the C-Span rankings, and James Buchanan fits the bill. This matchup is the nearest thing to a sweep even without close scrutiny of the elder Bush’s record. Buchanan, the final president before Lincoln, gets a single point for his strict constitutionalist approach to the slavery issue. Yet even this is a mixed bag—like Andrew Johnson, Buchanan could be said to be consistently not up to the task. Like Ford, Bush must wait for a tougher test in the next round.

Final result: Bush wins, 6-1.

Teddy’s Quarter—Round of 32

(4) Theodore Roosevelt vs. (36) Herbert Hoover

Teddy Roosevelt’s personality defined an age of American politics. On paper (and according to C-Span) it is hardly a fair matchup.

Not only does Roosevelt boast a strong record, but he wins many categories by default. Externalities, prosperity, crisis management, can all be given to him practically without debate simply on the basis of Hoover’s poor showing in these fields. Nor would any argue that Roosevelt lacked a clear picture of what America’s place in the world was—again, he defined American spirit at the turn of the century.

Hoover lands a couple of punches here. His record out of office still trumps Roosevelt’s. I would suggest that the charge up San Juan Hill, while commendably courageous, lacked the impact of Hoover’s humanitarian work. Given that Teddy brought vigor and ambition to the presidency which the founders likely would have distrusted, I give Hoover the point for consistency as well. Still, this one never feels close.

Final result: Roosevelt wins, 5-2.

(5) Dwight Eisenhower vs. (28) Gerald Ford

When I was in high school, my history class once did a presidential bracket exercise similar to this one. In my bracket, I had Eisenhower as the champion. My reasoning at the time? He ended the Korean War, which by 1953 involved Chinese troops and may have escalated quickly into a war with China and then with the nuclear-armed Soviet Union.

I realize now that my logic was slightly oversimplified, but Eisenhower still boasts a strong record. His ending of the Korean War and his generalship in World War II have him off to a fast start. Despite the Cold War, he presided over a generally prosperous eight years.

Part of his vision for America that he gets credit for is his valedictory warning about the “military-industrial complex”. Yet he did much to contribute to the growth of that same interest group during his time in office. He also endorsed the “domino theory” of communism in southeast Asia. Though ultimately correct, this theory served as a justification for escalation in Vietnam under other presidents. A point for Ford on externalities.

Another part of that vision—American inclusion in NATO—was contradictory to Washington’s advice for the nation of avoiding permanent foreign alliances. Thus, I also give Ford the point for consistency.

Ultimately, Ford’s record simply isn’t enough to make this a close-run affair.

Final result: Eisenhower wins, 5-2.

(12) James Monroe vs. (21) George H.W. Bush

This appear doesn’t appear to me as close-run as the C-Span-based seedings suggest. While Bush was a solid president, there are simply too many holes in his record. Monroe’s tenure was literally described as the “Era of Good Feelings”, and the Monroe Doctrine set boundaries against European involvement in the American hemisphere. On this basis, Monroe gets points for his bipartisan cabinet, prosperity, foreign policy, and vision, at which point the race is practically over.

I do, however, give Bush credit for his service as CIA Director and vice president under Reagan. Yet it is not enough to move the needle.

Final result: Monroe wins, 6-1.

(11) Woodrow Wilson vs. (20) Ulysses Grant

A perfect matchup: two presidents with significant strengths but also key vulnerabilities.

Given the corruption of the Grant administration, Wilson gets points for cabinet. A former academic, Wilson was the first president to articulate clearly the differences between the progressive platform (which he endorsed) and the original framework of the constitution. (A fascinating but critical overview of Wilson’s positions is found in George F. Will’s The Conservative Sensibility, which I include on my list of recommended books.) As a result, Wilson clearly had a vision for the country.

Yet this is a double-edged sword. The radical difference between Wilson’s progressivism and America’s founding principles hands the consistency point to Grant. Grant’s service in the Civil War nets him another point. At a 2-2 tie, this one is set to come down to the wire.

Prosperity and externalities are split. Wilson’s creation of the Federal Reserve brought an instrument of Keynesian monetary policy into the federal purview. While the “Fed” has a mixed record, it cannot be entirely dismissed as ineffective or unhelpful. To be fair, I give Wilson the prosperity point for the Fed’s good effects, and Grant the externalities point for its bad ones. I feel this is acceptable given that Grant also generally avoided major policy errors that predecessor had to clean up. The high school-level rundown on Grant is as a president who enabled corruption in his cabinet—but we’ve already considered that.

3-3. Who takes it? It comes down to foreign policy & crisis management. One might assume this to be a shoe-in for Wilson. While wartime presidents are doomed to make mistakes, Wilson was able in large part to keep America out of World War I. Yet at the peace table, Wilson contributed to the self-righteous aura that irritated both allies and foes, and his broad, vague demands in the Fourteen Points created a major snafu at the negotiations. Germany had already agreed to peace terms along the lines of Wilson’s points when British and French interventions ensured a far more draconian peace.

While Grant’s foreign policy record is far less prominent, he was the first president to suggest a trans-oceanic canal (ultimately at Panama). In the throes of reconstruction, his administration was also in a perpetual state of crisis. Through this, Grant was mostly able to ensure enforcement of civil rights legislation passed following the Civil War—under his successor, Hayes, these enforcements would severely fade.

This single point is the toughest one so far of the tournament, but I’m giving it to Grant. Sure, he lacked a true foreign policy crucible to be tested in, but the issues of reconstruction were challenging enough, and he generally rose to the challenge. Wilson, meanwhile, was able to limit American deaths in a major war, but failed to maintain his goal of neutrality. At the peace table, he overstepped the appetite of his own electorate for internationalism, and endured the embarrassment of his own country rejecting involvement in his progressive pet project, the League of Nations. This is simply too much. Grant wins, by a hair.

Final result: Grant wins, 4-3.

Teddy’s Quarter—Round of 16

(4) Theodore Roosevelt vs. (20) Ulysses Grant

Fresh off a nail-biter, Grant must now face the quarter’s top seed. This one has a close score line, but never feels in doubt.

There doesn’t appear to be any major dispute on Roosevelt’s points here. His progressive vision, his toughness on business’ monopoly powers, general avoidance of major externalities, and less scandal-ridden cabinet are all fairly clear winners. On Grant’s points there is likewise little contention. Grant’s generalship was invaluable in the Civil War, his policy stances were noncontroversial relative to the Constitution, and he was able to manage reconstruction better than Andrew Johnson had. There doesn’t seem much doubt as to the score line here.

Final result: Roosevelt wins, 4-3.

(5) Dwight Eisenhower vs. (12) James Monroe

This one is close and feels every bit of in. We’re talking overtime, down to the wire, both teams out of time outs.

Both Eisenhower and Monroe were presidents of outstanding foreign policy vision. The Monroe Doctrine has been a cornerstone of U.S. policy for almost 200 years. Eisenhower, meanwhile, ensured American participation in NATO and ended the brinkmanship over Korea. Therefore, I give foreign policy to Eisenhower and vision for America to Monroe. 1-1.

Here, Eisenhower stumbles. His foreign policy mistakes are fresher in our memories. Specifically, his endorsement of potentially committing American troops to die in the event of an adversary attacking France (or another NATO member) goes against the likely preferences of America’s founders, especially Washington. Further, this commitment, though arguably necessary at the time, has taken on new relevance since the Cold War ended. Since 1991, a more expansionist NATO has provoked a violent response from Russia in the Ukraine—something Americans should understand better given our own insistence on the Monroe Doctrine in our own geographic neighborhood. Because of this—and the domino theory over Vietnam, the externality point also goes against Eisenhower. 3-1, Monroe.

Yet Eisenhower isn’t down and out. His service during World War II remains exemplary, earning him another point. And we owe our interstate highway system to the National Highway Act, one of the most enduring and taken-for-granted public works projects in American history. Tied. 3-3.

Again, it comes down to the cabinet. Each cabinet contained a future president: Richard Nixon as Eisenhower’s VP, and John Quincy Adams as Monroe’s secretary of state. Given that Adams made it to the round of 32 in this tournament and Nixon did not, I give the edge to Monroe, ever so slightly. That’s enough to tip the balance, and the Virginian moves on.

Final result: Monroe wins, 4-3.

Quarterfinalists in Teddy’s Quarter:

- (4) Theodore Roosevelt

- (12) James Monroe

Join us next week for the conclusion of our presidential madness!