This article is part of a series on American history. Cross-reference to chapters 11 and 12 of A Patriot’s History of the United States and chapters 10 and 11 of A People’s History of the United States.

In the post-Reconstruction period, real controversies emerge among competing historical narratives—and reasonably so. Industrial titans (Andrew Carnegie in steel, John D. Rockefeller in oil, and J.P. Morgan in finance) amassed great fortunes. Factory laborers benefitted from the general economic growth as consumers (technology and corporate scale drove lower prices in many cases, as Patriot’s cites) but not as laborers. Working conditions remained harsh. In my appraisal of history, I would consider the final quarter of the 19th century as the low point for labor in terms of its bargaining power relative to capital—due to the unspecialized nature of many factory jobs, the absence of legislative protections that workers would often have to fight for, the lack of entrenched organized labor interests, and a heterogenous working-class population consisting of mostly unskilled workers.

Out of this sprang forth the “progressive” political movements of the early 1900s. The 20th century would eventually see the pendulum swing the other way: the diverse set of jobs available in a service-driven economy, new laws around working hours and working ages, large and powerful labor unions, and emphases on higher education and labor specialization. But on this point, we get ahead of ourselves.

By now, we shouldn’t be surprised that People’s devotes two entire chapters to various labor movements conflicts that occurred during this period. A key message of Zinn’s is both clear and accurate: many of labor’s gains were earned through strikes—often violent ones. The poignancy of workers’ grievances is shown in the strong showing of socialist and left-wing populist political organizations during the 1890s. Patriot’s address a few of these factors as well, although in less detail.

Again, my strongest criticism of People’s is its omission of large swaths of historical matter that I consider important—the accelerating settlement of the west, the shifting political winds between the parties, and the emergence of America as a potential great power. It is even silent on the conflicts with western Indians, outside a passing reference to Wounded Knee. Each of these are subjects that Patriot’s covers in depth.

In sum, our authors differ in what they focus on—what else is new? It’s all still important to the American story, and it’s our task to synthesize what’s most relevant in a small amount of space.

“Go West, Young Man!”

Most of what our authors mention regarding the eventual settlement of the American west comes from Patriot’s. Unsurprisingly, Schweikart & Allen take a limited government view. The two major transcontinental railroads (Union Pacific and Central Pacific) were given government aid, but Patriot’s touts James J. Hill’s privately-funded lines as being both more efficient and more resilient in economic panics. In a similar vein, it suggests that overharvesting of natural resources often occurred because of government subsidies and grants, which created distorting incentives that the market would ultimately have corrected. The American Western genre has contributed to the assumption that the “Wild West” was incredibly violent, but studies suggest that the homicide rate in frontier towns was similar to that of modern-day Washington, D.C.

Patriot’s also gives a fairly comprehensive account of the Indian wars on the Great Plains. These Indians, like the Sioux, were predominantly nomadic hunters following the bison herds. A contemporary traveler wrote: “Without the buffalo they would be helpless, and yet the whole nation did not own one.” Patriot’s cites sources dispelling the “ecomyth” that portrayed the Plains Indians as “the first true ecologist and environmentalists,” and explains: “Traveler after traveler reported seeing herds of rotting carcasses in the sun, often with only a hump or tongue gone.”

The U.S. Indian policy during this time debated between three schools of thought, each with their own advocates: preservation, extermination, and assimilation. The first two mutually incompatible ideas were described as “unrealistic” by Patriot’s, with assimilation left as a middle ground: “the only alternative to extinction, but it destroyed Indian culture…as critics rightly charged.” The incoherence of Indian policy was rooted in a civilian Bureau of Indian Affairs tasked with setting policies, which were dependent on the U.S. Army for execution. Patriot’s details events familiar to students of history: Sand Creek, Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee. The end result was the Dawes Plan in 1887, which set out to divide many reservation lands in 160-acre plots available to the Indians already living there. Contemporaries called this the “Emancipation Proclamation for the Indian”, although some unclaimed lands were stolen by speculators.

Patriot’s closes its discussion of the late-19th-century Indian wars with an equivocation: “It would be unwise to declare a happy ending to a 400-year history of warfare, abuse, theft, and treachery by whites, and of suffering by Indians. Yet it is absolutely correct to say that the end result of Indian-white cross-acculturation has been a certain level of assimilation, an aim that had once seemed hopeless.” No doubt Zinn, had he addressed the subject, would have excoriated this vacillation as indicative of the problem, and one’s views on Indian history will often boil down to that key question: at what cost does “progress” cease to be worthy of such a name?

The Last of Small Government

While Hayes entered office under spurious circumstances (see our last post), he nevertheless acquitted himself well in trying to rein in the corruption and patronage that the spoils system had fostered. This included an investigation into alleged corruption at a New York customshouse led by Chester Arthur. Ironically, Arthur would become president in 1881 following the death of James Garfield (who succeeded Hayes), and in 1883 would sign the Pendleton Civil Service Act, considered “the deathblow to spoils.” The Republican Party had a growing contingent of reform-minded members, and this was reflected in national policy.

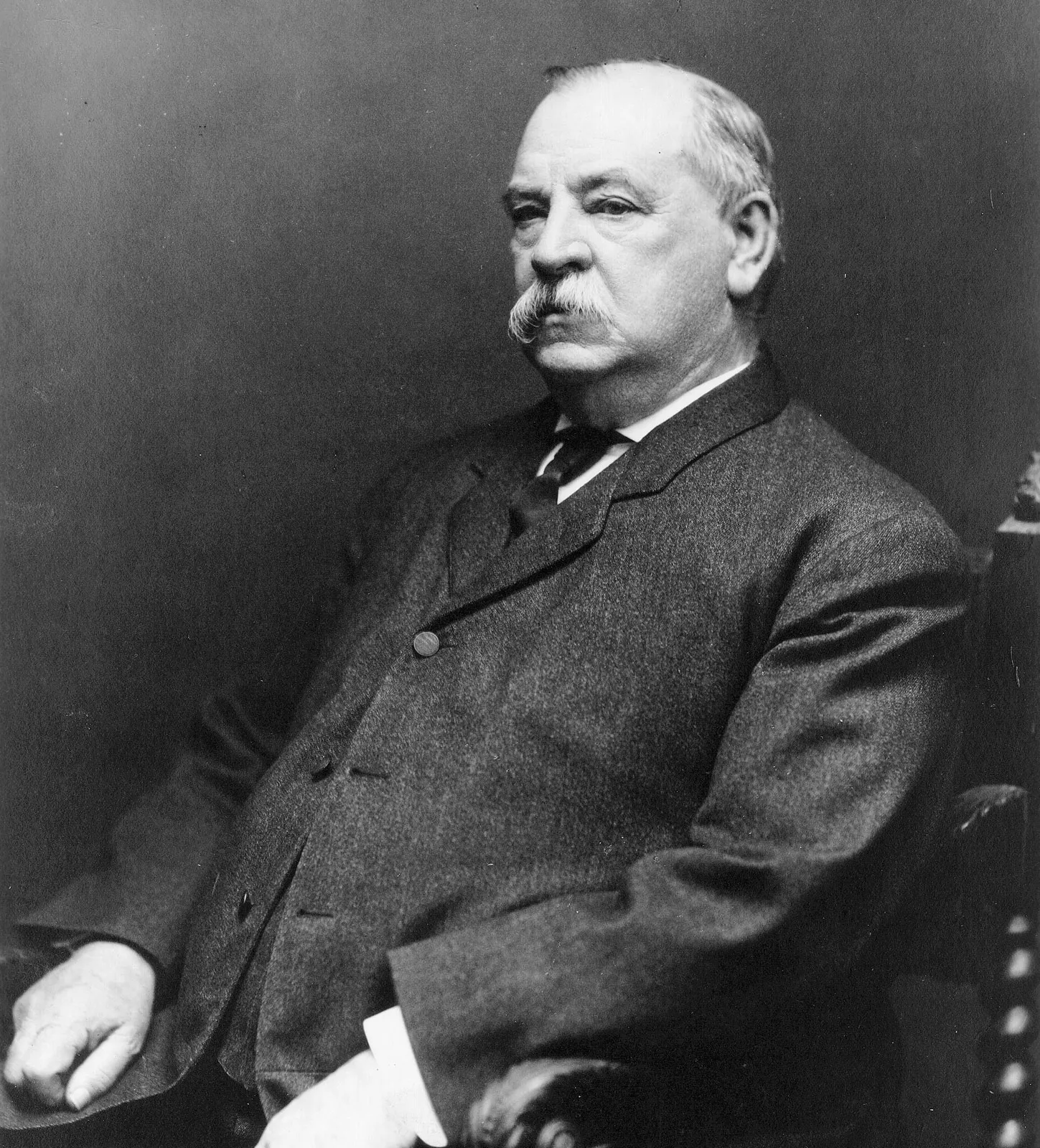

Grover Cleveland was the only Democrat elected president between 1860 and 1900, winning non-consecutive terms in 1884 and 1892 (with Republican Benjamin Harrison in between). Patriot’s claims that Cleveland has been overlooked by modern historians “because he simply refrained from the massive types of executive intervention that so attract modern big-government-oriented scholars.” Governing by principle rather than party interests, he insisted on a strict enforcement of the Pendleton Act, and cracked down on fraudulent pension claims intended for Civil War veterans. In his second term, he vetoed a bill that would have provided federal loans to farmers to buy seed corn, insisting that the federal government had no such power to intervene on economic questions.

Benjamin Harrison likewise “hoped to restrain the growth of government,” although he signed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, which, though lacking specifics, would ultimately be used to prosecute Standard Oil, AT&T, and Microsoft. Harrison also spent heavily on modernizing the U.S. Navy with modern steel cruisers.

The key economic debate of the era revolved around the monetary system: whether it should rely exclusively on gold-backed dollars (limiting inflation) or include greater quantities of silver-backed dollars (which would allow greater money circulation, helping indebted farmers but also causing general inflation). Cleveland opposed introduction of silver, and sought to limit and repeal existing legislation authorizing government purchase of silver at artificially high prices. The financial panics of the 1890s caused such a drain on federal gold reserves that banker J.P Morgan had to bail out the government with a loan. In this sense, Cleveland’s conservatism was found wanting by voters at the time, and the 1896 election in many ways represented the peak of economic discontents harnessed by new populist political movements—something not truly repeated until 2016.

“Capital and Labor Stand Opposed”

This subtitle is a quote from an 1840s Massachusetts workers’ newspaper, and predates the Communist Manifesto by four years. People’s claims that standard textbooks of history contain “little on the class struggle in the nineteenth century.” Zinn is most likely correct on this. He cites several movements of labor going back prior to the Civil War:

- The Anti-Renter movement in New York against wealthy landlords (1830s)

- Dorr’s Rebellion demanding an end to property qualifications for voting in Rhode Island (1841)

- The Flour Riot in New York (1837)

- The railroad strikes of 1877 in which 100,000 workers went on strike

These, along with more well-known points of labor unrest like the Haymarket Riot in Chicago, are anomalies to Patriot’s, but the key part of the picture to People’s, who cites Marx’s earnest attention to labor movements in America and his hope they would lead to the formation of an “earnest workers’ party.”

Patriot’s provides further statistics to put the Gilded Age’s inequalities in context. Schweikart & Allen cite three studies of wages in the late nineteenth century, each of which point to real incomes increasing for urban laborers, roughly doubling between 1867 and 1893. The richest Americans “held between 300 and 400 times the capital of ordinary line workers, creating perhaps the greatest wealth gap between the rich and middle class that the nation has ever witnessed.” Patriot’s mentions a massive increase in the number of millionaires. People’s retorts that “while some multimillionaires started in poverty [Carnegie, Rockefeller], most did not,” and recalls a study of industrial executives in which 90% came from middle- or upper-class backgrounds.

Patriot’s also claims that businessmen “as a class” were roughly 112 times more productive than the lowest-paid laborers. While this statistic is spurious at best, it raises a critical question: what is the preeminent source of economic value? Is it labor, as Marx would claim, or is it capital? This remains a slippery question.

We need not belabor this point, but we can suggest the following explanation: the changes in technology demanded adaptations to capital before demanding the same of labor. Steel mills, railroad lines, and oil refineries could not be constructed or operated without large amounts of capital—money put at risk into new, unproven industries. To serve these industries, many laborers did not possess special skills or did not need them; put another way, there was no shortage of workers for America’s industrial enterprises. We can see evidence of this in examples both our authors cite of workers both willing and able to break with their striking brethren and resume working. Labor clearly lacked the bargaining power that capital possessed—a condition that is partly cyclical and was partly remedied by government actions.

It is likely impossible to objectively answer whether or not the United States experienced true “class struggle” in the Marxist sense during the late 19th century. People’s cites examples of riots and unrest; Patriot’s points to an overarching trend of rising wages and lower prices that benefitted everyone, especially the poorest workers. Ideology is inherently unobjective—that is, there is no benefit (or point) to “proving” an ideologue wrong. That said, a number of important political themes emerged from America’s industrial transformation, many of which are worthy of discussion here.

New “Isms”

As Patriot’s puts it, American progressivism did not flourish until the turn of the century but had its roots in the 1880s. Progressive reformers “embodied a worldview that saw man as inherently perfectible” but were often from wealthy families and “were people who seldom experienced hardship firsthand”—phrases conjuring images of the intellectual arrogance and cowardice that characterizes America’s universities today. Concepts like “social Darwinism” and sociology itself were proof that progressives put the “science” in the social sciences—a place where many still feel it has no place.

Labor unions, considered illegal until 1842, sprang up following the Civil War. The Knights of Labor, founded in 1869, grew rapidly by enlisting members regardless of occupations—numbering 700,000 in 1886. The Knights won several victories against Midwestern railroads, but their involvement in the Haymarket Square riots in Chicago—and the racial violence they perpetrated against Chinese immigrants who broke their strikes—marked their end as a force in organized labor.

By contrast, the American Federation of Labor, founded the same year as the Knights came to blows with the law in Chicago, took a different approach. The AFL focused on including skilled laborers, and as Patriot’s tells it, avoided involvement with political issues and focused on two objects: better wages, and better hours.

Farmers formed their own sorts of unions under the Patrons of Husbandry (commonly called Grangers), which soon evolved from a network of farm co-ops into a political lobbying group demanding regulation of the grain elevators and railroads they depended on. In the key Munn vs. Illinois case, the Supreme Court ruled that the state legislature had powers to regulate private property that was connected with the public interest. Patriot’s called this an “alarming” doctrine, while People’s bemoans that the ruling lacked teeth and was weakened by subsequent judicial decisions.

The economic depression in 1894 drew Eugene Debs into a “lifetime of action for unionism and socialism,” as People’s tells it. Debs aimed to unite all railway workers into a single union, and merged with the remnant of the Knights of Labor. Denying his socialist creed in court (and he spent a great deal of time either in court of prison), his writings were much more candid: “The issue is Socialism versus Capitalism. I am for Socialism because I am for humanity.” Debs ran for president multiple times, including while behind bars.

The origins of American populism were rural, as People’s describes them, with a group of Farmers’ Alliances that coalesced into a Populist party in 1890. Yet this was a national working-class movement that spanned divides: “northern Republicans and southern Democrats, urban workers and country farmers, black and white.” Above all else, the uniting factor was a sense of class indignation.

In the election of 1896, the Populist party promised enough electoral clout for the major parties to take notice. People’s describes, accurately, the dilemma the Populists faced when they aligned themselves behind William Jennings Bryan and the Democrats: “If the Democrats won, it [the Populist party] would be absorbed. If the Democrats lost, it would disintegrate.” Many radicals among the Populists sought to avoid such major-party compromises, but to no avail. Patriot’s suggests one reason for the Populists casting their lot with the Democrats: candidate Bryan’s strong rhetoric around the abolition of the gold standard, which would have provided the silver-driven inflation many farmers had advocated.

To Zinn, the eventual victory of Republican William McKinley was a tragedy—a missed opportunity for real economic change. Instead, “it was a time…to consolidate the system after years of protest and rebellion.” For better or worse, McKinley’s victory was a watershed moment in American history. One of America’s great demagogues, Bryan likely would have embarked on aggressive economic policies that would have continued the turmoil of the previous three decades—regardless of their ultimate efficacy. Instead, Bryan was left with Henry Clay and Hillary Clinton on a list of American politicians that managed to leave a true mark on history without winning the presidency. McKinley would turn American energies abroad at an auspicious and critical time.

In our next post, we’ll cover the turn of the century and the first World War.