This article is part of a series on American history. Cross-reference to chapter 9 of A People’s History of the United States, and chapters 9 and 10 of A Patriot’s History of the United States.

Aside from the Revolution, the Civil War was the defining moment in American history, engaging deep principles and challenges regarding racial equality, human rights, constitutional law, and partisan interests. It is also among the most misunderstood. Because of such an intersection of factors and the complexity of the events and individuals involved, it’s easy to interpret the history based on preconceived notions and biases. Part of this is inevitable—but it is nevertheless our job to try & cut through the bias and the noise as best we can.

Unsurprisingly, our authors take different angles in their approach to the war and its aftermath. Patriot’s devotes a long chapter to the events of the war, while People’s makes nearly no mention of war events. People’s does claim that Lincoln “initiated hostilities” by sending federal ships to reprovision Fort Sumpter in South Carolina—a claim that Patriot’s refutes by naming the very Confederate individual who fired the first shot.

People’s stresses more than Patriot’s that Lincoln’s primary objective in the war was to preserve the Union rather than end slavery, a point cited in a letter from Lincoln to editor Horace Greeley. Both authors cite the practical need of keeping the border slave states in the Union.

The Wartime Confederacy

We mentioned in our last post a comment of Jefferson Davis accusing the free-soil party of opposing the south for reasons other than slavery. Yet the Confederate vice president took a different line: “Our new Government is founded…upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man. That slavery—subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.” For Patriot’s this was enough to conclude that the Confederacy was founded on slavery as a moral and positive principle.

Patriot’s also cites that the tribes in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) also joined the Confederacy, although little is mentioned about their reasons for doing so or their contributions—or lack thereof—in the war that followed.

The Confederate constitution was ostensibly Jeffersonian—it prohibited tariffs and subsidies, and required a two-thirds majority for all spending or tax bills. In practice, Patriot’s cited the “de facto subsidies to slave owners” due to the costs of slavery foisted upon law enforcement and the court system. Other provisions—a line-item veto and lack of a central independent judiciary—left virtual dictator powers in the hands of Jefferson Davis. Like Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, the Confederacy fell well short of the Jeffersonian ideal.

Nearly a quarter of the rebel troops were either drafted or paid substitutes of draftees—relative to less than 8% on the Union side. Patriot’s uses the phrase “state-dominated economy” to describe the wartime south: “While the North skimmed off the top of private enterprise, the South, lacking an entrepreneurial base to match, was forced to put the ownership and control of war production in the hands of the government.” While Patriot’s takes a clear line that big government was a product of the war on both sides (explaining changes in the north’s banking system that remained following the war and increased the risks of postwar financial panic), the Confederate war economy was far more state-run.

The Union forces included free black soldiers—they made up around 9% of the army, according to Patriot’s. Both our authors speak to the initial discrepancies in pay between black and white soldiers: $10 a month minus $3 for clothing for blacks; $13 a month plus clothing for whites. Yet Patriot’s clarifies that the pay inequity was addressed by Congress in June 1864—a point People’s does not mention.

The War Itself

In interests of space, we won’t provide a comprehensive overview of the events of the war itself. This is certainly not to say that the events aren’t important, or that I do not find them interesting—quite the contrary. Indeed, I feel that to do the war justice would require an entire series of articles at least equal in length to these, and I do not want to give it short shrift.

I will, however, provide a couple of alternate sources with sterling recommendations. The first was brought up in our previous post: The Civil War: A Narrative by Shelby Foote. This is one of the most thoroughly researched and objectively written history projects I’ve had the pleasure of reading. It provides incredible detail on both the key battles and campaigns of the war and more overlooked theaters and motivations of key actors. It is an endurance act to finish: ~700,000 words, or over 130 hours on Audible—but well worth the effort.

For those understandably put off by the volume of Foote’s work, here’s a much more accessible account. YouTuber Oversimplified has an excellent 2-part summary of the Civil War’s roots, events, and immediate aftermath. While being less than an hour in length, this overview is entertaining without sacrificing much accuracy or insight.

In ending its summary of the war events, Patriot’s turns again to asking what it was all for, citing two common narratives. The first is the “Lost Cause” myth that rebrands the Confederacy as standing for states’ rights and limited government principles, but ultimately undone by the power of the oppressive Union government, which imposed a corrupt Reconstruction to subjugate the south. Schweikart & Allen claim this argument receives support from some “modern libertarians who…viewed the Union government as more oppressive than the Confederacy,” who argued that the south would eventually consent to abandon slavery. Yet this misses the point that the Confederate government was in fact more intrusive than the Union one during the war, and that throughout human history, slavery was “seldom voluntarily eradicated from within.”

With the same breath, Patriot’s criticizes the “neo-Marxist” interpretation endorsed by Charles Beard, People’s, and others, which claimed the Civil War was meant simply “to retain the enormous national territory and market and resources” of the united nation. Patriot’s insists that the “free market” was the “only hope for many Southern blacks”, and claims that “the government, and not the market, perpetuated Jim Crow.” To me, Patriot’s seems to miss the point: in representative government, the market and the government exist to serve the same populations—therefore preferences of the people that a government doesn’t recognize will find their expression in the market. Southern whites largely retained their preexisting prejudices after Appomattox, and early in Reconstruction, when Republicans held strong positions in southern state governments, only federal troops were able to maintain any semblance of equality.

Yet this critique doesn’t touch the fundamental purpose of the war as Patriot’s saw it: “the idea of freedom.”

One Government, Now Divided

A week after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. With this tragic turn of events, the nation was deprived of his wisdom just as it faced the crucial task of rebuilding from the war.

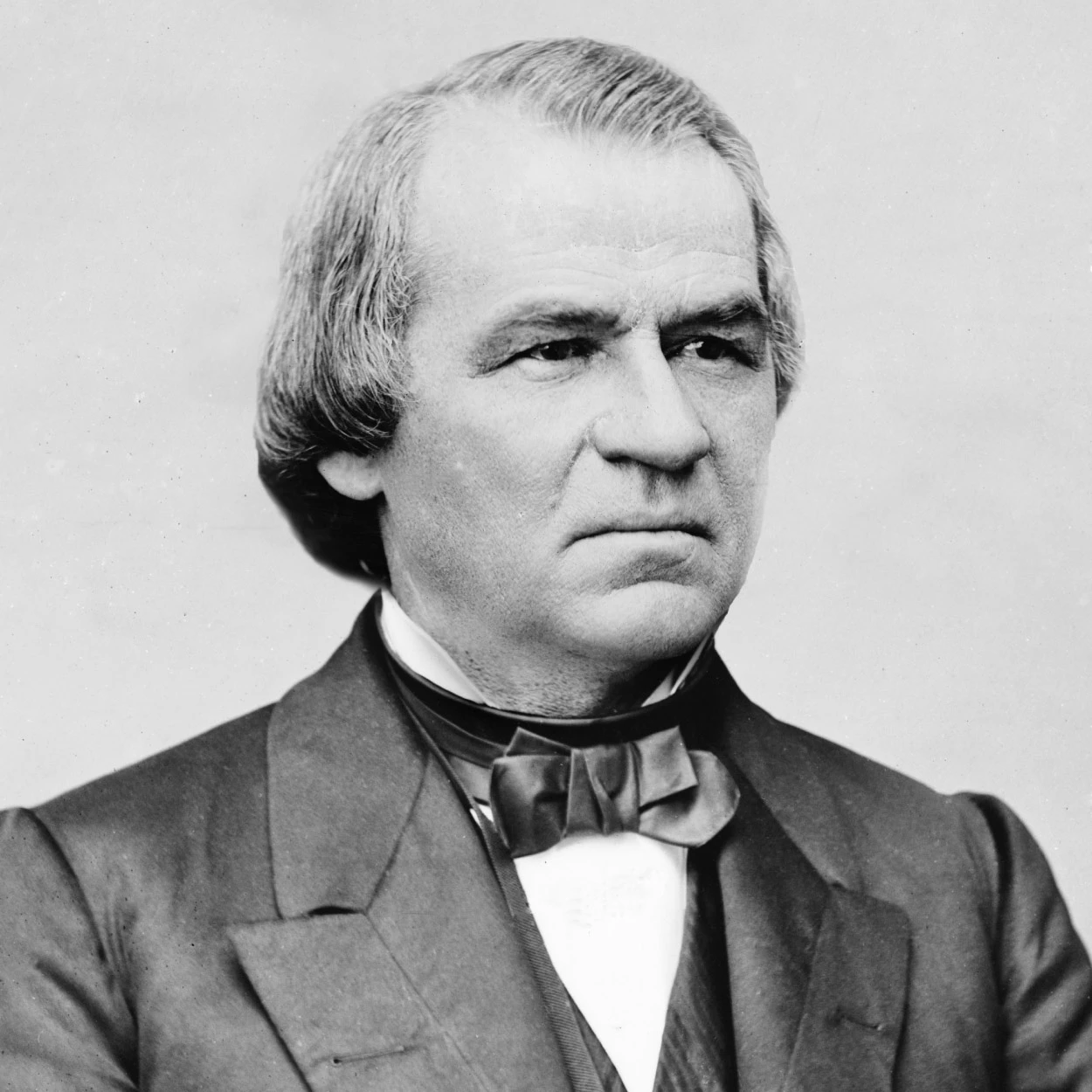

Thrust into the presidential role was Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat who had refused to support secession. Selected as Lincoln’s running mate to entice war-supporting northern Democrats to support Lincoln in the 1864 election, Johnson was suddenly expected to carry out the policies of the Republican-dominated Congress. Patriot’s details Johnson’s predicament: “he had no goodwill upon which to draw.”

Compounding Johnson’s difficulties was an influential radical group of Republicans in Congress. The radicals sought “not only to incapacitate the South as a region, but also to emasculate the Democratic Party.” Patriot’s criticizes their motives, claiming the radicals saw both the freedmen and the white southerners as political pawns to manipulate for their own aggrandizement. Radicals supported the redistribution of confiscated southern property to favor the freed slaves. People’s saw the importance of such a policy, recognizing that postwar prosperity was dependent on land ownership. Yet Patriot’s took a legalistic approach to this, suggesting that confiscation of southern property as punishment for slavery would have applied an ex post facto enforcement of laws, something specifically prohibited by the Constitution. Union General Sherman had ordered land in South Carolina to be confiscated for the settlement and ownership of freed slaves—but Johnson rescinded this order. Johnson’s efforts to placate former Confederate leaders enraged the radicals. Criticisms of Johnson ranged from “stubborn moderate” to “reactionary”, but one point is clear—he could not work with the radicals in Congress.

The radicals supported the creation of the Freedmens’ Bureau, a new government agency that provided for education and other services to former slaves. The Bureau sought to prevent Confederate amnesty provisions (a policy of Johnson’s) from being applied to confiscated land. This was an instance of an executive branch entity seeking to “hijack” the policy of the president for different policy ends—and Johnson quashed such efforts.

In hindsight, Lincoln’s political savvy of including a Democrat on the ticket, while helping to win the 1864 election, ultimately doomed the first few years of Reconstruction. Johnson and the radical Republicans were at complete loggerheads, and the radicals sought to impeach him. The charge was a spurious one—seeking to define as “high crimes and misdemeanors” the act of defying a Congressional overreach preventing Johnson from firing his cabinet. Despite the weakness of these charges, the fact that the Senate trial came only one vote short of the two-thirds needed to convict sheds light on the intense radical feeling and influence present in Congress at the time.

Liberty Under Guard

Throughout the south, blacks began, for the first time, to exercise the right of the ballot. Indeed, our authors both point to instances of black agency in the postwar years. Land ownership remained elusive but not entirely—by 1890, black land holdings in North Carolina reached 19% of the total in a study Patriot’s cites. In South Carolina, the lower house of the legislature soon held a black majority. In South Carolina, the black voters supported free public schools, introduced to the state soon after the war, and also quadrupled the public debt of the state by 1873.

The surge in black participation in elections was made possible by Constitutional amendments that outlawed slavery and ensured “equal protection of the laws”. While these, along with the Civil Rights Act (which Johnson vetoed in vain) gave blacks citizenship status de jure, the presence of federal occupation troops guaranteed the rights in practice. People’s cites two black senators and twenty black representatives in Congress, although this was a high-water mark that faded quickly after the departure of federal troops in 1876—with no blacks remaining in Congress in 1901.

Parallel to this trend was another, contradictory one: despite the military occupation and Republican-dominated Congress, mob violence, vigilante justice, and the terror activities of groups like the Ku Klux Klan represented a south that neither admitted guilt nor accepted racial equality. When legal challenges to such extra-judicial discrimination reached the Supreme Court, they were usually defeated—taking the teeth out of the Civil Rights Acts that were meant to ensure legal equality. “Redeemer” Democrats sought control of southern state governments, with the principal issues of “race, race, and race” according the Patriot’s. Led by former Confederates, the Democrats in the south adopted black codes restricting freedom of travel and freedom of labor contracts, and also repudiated all state debts—a move that Patriot’s claims helped to “condemn the South to decades more of poverty.”

“At Least it’s not Johnson”

This was probably the attitude of the radical Republicans in 1868, when they nominated war hero Ulysses S. Grant as their presidential candidate. Grant had the advantage of being a household name without any political baggage—and therefore he won handily, with 500,000 black voters contributing to the outcome.

Lacking political baggage, Grant equally lacked political talent. He retained many of the small-government notions of the old Whig party, which left him unprepared to combat the corrupt schemes of many of his friends. Some speculators attempted to corner the gold market, causing a financial panic. Others manipulated federal grants to railroad companies to siphon money away from the federal government. Grant was rightly criticized for these by historians, yet Patriot’s insists that many of these criticisms miss a key point. “Such corruption tracked precisely with the vast expansion of the federal bureaucracy,” and “it was an orgy of government intervention that caused the corruption and fed it.”

In Grant’s re-election in 1872, a powerful “Liberal” faction emerged in opposition to the radicals, nominating ardent reformer Horace Greeley as their candidate. While the Liberals failed to unseat Grant, they helped redefine the Republican Party around stances of free trade, small government, sound money, and light fiscal spending.

The growing unpopularity of radical Reconstruction measures helped the Democrats, already in control of many southern states, to gain control of the House in 1874, making further Reconstruction reforms difficult at a time despite the continued military occupation of some states. In 1872, Congress passed the Amnesty Act, which allowed former confederate leaders to vote and hold office. Patriot’s admitted that the effect of this was for the north to “abandon what it started.”

Hayes: Great Compromise, or Corrupt Bargain?

In the 1876 election, Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes found himself in need of three contested southern states to win—Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. Hayes fully expected to lose the election, and he lost the popular vote by 3% to the Democratic candidate. Despite the likelihood of ballot fraud in the south (almost certainly favoring the Democrats), he didn’t contest the election. Republicans in the south countered with ballot manipulations of their own.

Congress appointed a bipartisan commission to determine the winner in the three disputed states—but the sole independent voice on the committee refused to serve, and was replaced by a Republican. Thus, the official commission found Hayes the victor in all three states, surprising no one.

At the same time, Hayes’ associates brokered a deal with the Democrats, agreeing to include southern Democrats in the cabinet and remove all remaining federal troops from the states in question. Patriot’s cites this as a misperceived “great compromise”, when the official results would have simply confirmed Hayes’ victory. Accusations of a corrupt bargain followed, and Hayes “faced almost insurmountable odds against achieving much.” The practical implications were Reconstruction were clear: without federal troops remaining in the south, Reconstruction was effectively over. Without the bayonet protecting the ballot box, southern states fell into varying states of backsliding on rights for former slaves.

What Might Have Been?

People’s takes a critical stance on Reconstruction, suggesting that it never lived up to the lofty principles it sought to achieve. This is a fair criticism, yet Patriot’s underscores the fact that generations of prejudice cannot be erased through the force of law. This was why the radical Republican attempts at complete equality couldn’t be realized except through military occupation—and when the north lost the energy for continuing the occupation, it forfeited many potential civil rights gains.

The fact that Reconstruction fell short is clear. But how we modify that view depends heavily on another question: what is it fair to expect from human nature? Can the sheer will of a government—any government—change the minds of its people, for good or ill? And if it can: should it?

In our next post, we’ll cover the “Gilded Age” of economic expansion, railroads, and changing labor relations.