This article is part of a series on American history. Cross reference to chapter 8 of A Patriot’s History of the United States, and chapter 9 of A People’s History of the United States.

Following the Mexican-American War, sectional differences—north vs. south, free states vs. slave states—came to define nearly every national issue. The acceleration of such disputes in the 1850s rendered reconciliation impossible. When Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, he did not win a single southern vote, and the Van Buren political framework failed. Patriot’s cites that this was partly made possible by high rates of immigration (Irish and German immigrants were the first to come in large numbers) that flowed to the north and northwest rather than the south.

My original intent was to take the pre-Civil War decade, the Civil War itself, and the following decade of the Johnson and Grant administrations together in a single post. However, given the import of America’s greatest national crisis, our authors both have quite a bit to say. Patriot’s devotes three chapters to the subject: one pre-war, one on the war, and one post-war. People’s only takes one chapter, but it is long: twice the length of many of its others. Not only that, but they mention many of the same things, with different perspectives. In some cases they agree—although likely in ways that would have surprised them.

Because of all this, I am now expecting that this period will require two posts. All else equal, I would prefer two slightly shorter posts that thoroughly address the relevant points, rather than a single post that is both long and crammed. That’s enough preamble: we begin with an examination of slavery as told by our authors.

The Incomplete Explanations of Economy and Race

People’s sets an appropriate tone, referencing (and disparaging) economical or statistical analyses of slavery such as those that “have tried to assess slavery by estimating how much money was spent on slaves for food and medical care.” Zinn dismisses such analysis: “Are the conditions of slavery as important as the existence of slavery?”

Patriot’s voices the same sentiment, asserting that “even the most ‘benign’ slavery” was “always immoral and oppressive.” Yet Schweikart & Allen do cite a few basic numbers. In 1860, about 10% of Virginia blacks were free. In South Carolina in the same year, 171 free blacks owned over 700 slaves. Patriot’s also cites a study of recollections from former slaves which estimated about a third of slave families were separated.

Both authors criticize statistical historians Fogel and Engerman, who in Time on the Cross estimated that slaves were whipped an average of 0.7 times per year. Patriot’s calls this “antiseptic,” and People’s and Patriot’s both question the relevance and reliability of the data sample—a single plantation owner’s diary.

Yet, given their financial history backgrounds, the authors of Patriot’s seek to understand the economic rationale for slavery. They admit that “the capitalist mentality and the racial oppression” intermingled “to the point that the system made no sense when viewed solely in the context of either.” This is a complex answer that questions any attempt to demand a single explanation. Patriot’s cites estimates that the returns on capital of slavery were roughly 8.5% a year, compared with southern industrial firms which often generated returns well above 22%. In purely economic terms, such a discrepancy should have caused the “invisible hand” of market forces to kill slavery over time. Schweikart & Allen suggest that “dominance and control”—psychological “gains”—prompted slavery to remain entrenched: “The persistence of slavery in the face of high nonagricultural returns testifies to aspects of its noneconomic character.”

A Surprising Parallel?

Patriot’s also examines what southern politicians and intellectuals claimed to defend the institution of slavery. John C. Calhoun (we know him from our previous post, where he resigned the vice presidency to stand on the brink with his native South Carolina) claimed of slavery: “we now see it in its true light…as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.” To Patriot’s, this dovetails with the Marxist principle of the “labor theory of value”, in which economic value is a function of labor alone rather than a mix of labor and capital.

Virginia’s George Fitzhugh considered slavery and socialism “one and the same”, and advocated that “not only should all blacks be slaves, but so should most whites.” Fitzhugh insisted that “Liberty is an evil which government is intended to correct,” further asserting, as Patriot’s put it, that “northern wage labor was slave labor, while actual slave labor was free labor.” The basis for this was the idea that all contract labor was essentially unfree, and the slaves, being free from all decisions, enjoyed true “free laborer” status.

Fitzhugh was not alone in this view. In 1861, Harrison Berry wrote in Slavery and Abolitionism, as Viewed by a Georgia Slave: “A Southern farm is the beau ideal of Communism.” People’s is (of course) silent on any intellectual links between Marxist thinking and proslavery arguments.

The key difficultly in reconciling this challenging proposition is to avoid any attempt to shoehorn it into our preconceived notions of what history means. Modern socialists will be quick to insist that a few spurious rantings cannot be relied upon to create an indelible link between Marxism and slavery, while modern conservatives would likely insist (at equal volume) that such a connection reveals the “true colors” of organizations like Black Lives Matter as race-based fronts for communism in America. In my view, neither such interpretation is liable to be correct—but the examination at the very least should inform us that ideas are complicated, and dogmatic adherence to any ideology risks the forging of arguments that seem disgraceful to anyone outside that ideology.

It is also likely true, as Patriot’s puts it, that “religion and the law” were the key levers manipulated to justify and perpetuate slavery. People’s agrees, stating simply: “Religion was used for control.” Patriot’s strikes the theme of control as well, suggesting that the Nat Turner rebellion in 1831 convinced many southern churches to accept “the desirability of slavery as a means of social control.” Our authors both reference stern measures that virtually turned the south into a “police state”, as Patriot’s put it: “Censorship of mails and newspapers from the North, forced conscription of free Southern whites into slave patrols, and infringements on free speech.” These themes suggest another challenging idea: that social “order” is not the highest good in and of itself, and immoral sacrifices are often made to preserve that order in the short run. I would expect our authors to agree with such a sentiment.

How Did it Come to This?

Political attitudes in the south, according the Patriot’s rode a “roller coast of euphoria followed by depression” between 1848 and 1860. The gag on slavery debates in Washington was off, and the south lived in constant concern that a national government unsympathetic to slavery might eventually take power. America was particularly unfortunate to have a series of four presidents in this period (Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, Buchanan) that demonstrated little aptitude for high statesmanship.

That said, one of the great statesmen of the age, Henry Clay, harder made things any better. In his 1850 Compromise, California was admitted as a free state, Texas debts were assumed by the national government, and the status of Utah and New Mexico regarding slavery would be determined by residents of those territories—kicking the can down the road. The compromise passed through a series of unsteady votes, and president Fillmore called it a “final and irrevocable” settlement of the slavery issue.

One aspect of the compromise was the Fugitive Slave Law, that required northern law enforcement and private citizens to become essentially complicit in slavery. Patriot’s cites the law’s effect of “personalizing slavery to Northerners and inflaming their sense of righteous indignation,” while both authors cite instances of mob actions in Syracuse and elsewhere in response to the law. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin added gasoline to the bonfire of northern outrage when published in 1852.

Southern interests required for slavery to be expanded to the greatest extent possible. Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis (later president of the Confederacy) had his eye set on Cuba. Spain had already rejected an offer of $130 million for the island—a staggering price relative to Louisiana and the Mexican territories that likely reflected southern enthusiasm. At a conference in Belgium, American ministers drafted a secret memo suggesting that, in the event of a slave revolt in Cuba, the U.S. would simply take the island. This Ostend Manifesto caused some embarrassment when it became public. Other southern senators took even more expansionist views, suggesting that the fledging republics in Central America should be annexed to provide further space for slavery.

David didn’t need to fret over Cuba, however. Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which revoked the slave-free demarcation line of the Missouri Compromise and opened both namesake territories to determine the question by popular sovereignty. Douglas, a Democrat, had introduced the bill in hopes of securing agreement on a transcontinental railroad that would benefit his Chicago constituency. Instead, he shattered his own party, as the Kansas territory degenerated almost immediately into violence.

As the Democrat Party fell apart as northerners deserted the party in droves, the Whigs disintegrated for the same reason. Both parties had failed to take a definitive stance on slavery. This was about to change, however: Salmon Chase and William Seward organized the new Republican Party in 1855. While the Republicans continued, like the Whigs had, to favor tariffs and a national bank, there was no doubt as to the key party plank. Unlike the previous two-party system, this iteration of Democrats and Republicans centered around a single issue: slavery. The Republicans would be the first party to make slavery a moral issue and refuse to duck it on the national stage.

Judicial Non-Restraint and Jayhawks

The 1850s can be viewed as a series of events that forced slavery more and more into the national debate and public mind—essentially Van Buren’s nightmare. His party system had fallen apart, and the national parties were now divided over slavery, created what was tantamount to north-south blocs. Yet the nightmare was far from over.

In the Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court, under Chief Justice Taney, ruled against a slave named Dred Scott who brought a suit asserting his freedom based on his residence in multiple free states. Taney’s opinion, characterized by Patriot’s as that of a “Court overcome by hubris”, insisted that Scott had no right to sue since he was not a citizen. This ignored the legal precedents set in free states. Rubbing salt in the wound, Taney claimed blacks were “a subordinate and inferior class of beings [who] had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Meanwhile, the situation in Kansas reached a climax. Fraudulent elections were the norm in 1857 Kansas, and the state ended up with two legislatures, one proslavery, one free-soil, both claiming legitimacy. The proslavery forces had put forth a proposed constitution for the state, which permitted slavery in the territory. The Territorial Legislature, home of the free-soil advocates, demanded a referendum and voted decisively to condemn the constitution. President Buchanan tried to entice the free-soil forces to accept this constitution, holding out the carrot of federal land grants and brandishing the stick of delayed statehood if they didn’t accept. Kansas voters emphatically rejected any compromise, with the free-soil delegates rejecting statehood on any terms but legitimate ones.

The Northern Man of Northern Principles

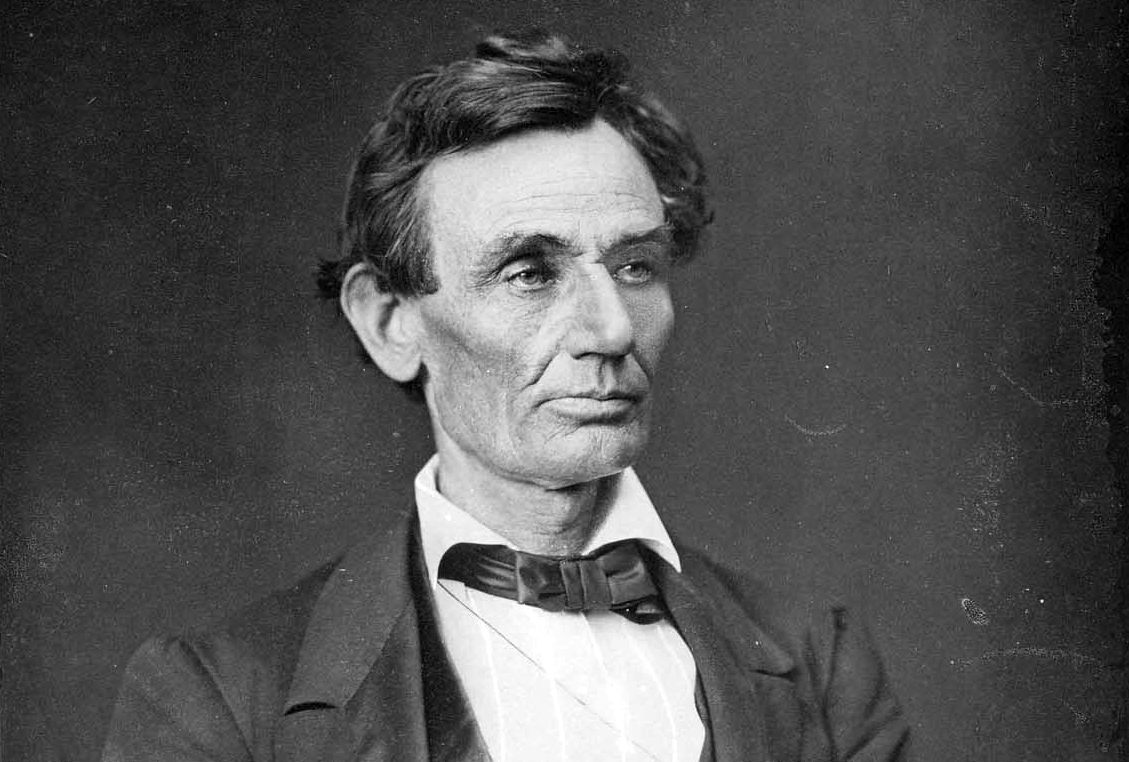

Patriot’s cites Senator Stephen A. Douglas as an example of a “value neutral” politician, one who sought to avoid the fundamental question of whether slavery was moral or immoral. He holds this in stark contrast to another Illinois congressman: Abraham Lincoln.

People’s takes a somewhat more cynical view of the sixteenth president: “It was Abraham Lincoln who combined perfectly the needs of business, the political ambition of the new Republican party, and the rhetoric of humanitarianism.” One questions the automatic categorization of Lincoln as representing monied interests given his poor farming background and the crushing business debts he had to pay off following the death of a law partner. Yet Lincoln did endorse much of the pro-business, pro-north agenda outside of slavery, stating in the 1830s: “I am in favor of the internal improvement system, and a high protective tariff.”

Much has been made of Lincoln’s supposed racism. People’s cites that Lincoln’s speeches took somewhat different stances on the subject of racial equality, with his speeches in northern Illinois tending to be more progressive than those in the south of the state—home to many Confederate sympathizers, or Copperheads, during the war. Patriot’s does not shy away from this, acknowledging that many of Lincoln’s comments are bound to appear unacceptable to our ears. Yet it also warns against the “historical flaw known as presentism”, and advises that “Such comments require consideration of not only their time, but their setting—a political campaign.” Lincoln had insisted on paying black and white soldiers equally in the Civil War, and went out of his way to make Frederick Douglass welcome at his second inaugural in 1865.

What Was It About, Really?

As Patriot’s saw it, Lincoln “placed before the public a moral choice that it had to make” when it came to slavery. This idea that the Civil War was primarily a question of slavery is a key argument of Schweikart & Allen who mention it in their preface: “Continued new research points to slavery as the overwhelming, if not sole, cause of the American Civil War, a position we took from the beginning.”

Not all would see the matter so simply. People’s cited economic greed as an important factor. “The northern elite wanted economic expansion—free land, free labor, a free market, a high protective tariff for manufacturers, a bank of the United States. The slave interest opposed all that.” Contradicting himself, Zinn also cites wealthy Boston conservatives who sought to appease the south “in the interests of commerce, manufactures, and agriculture,” suggesting that the interests of the rich were not so monolithic as he might hope.

Even if correct, Zinn finds himself in an awkward position, given that Jefferson Davis agreed with him. As Patriot’s put it, Davis and others “deluded themselves into thinking that Southern economic backwardness was entirely attributable to the North.” As Davis himself said: “You free-soil agitators are not interesting in slavery…not at all…You want to promote the industry of the North-East states at the expense of the people of the South and their industry.”

Zinn also has some half-support from Shelby Foote, author of The Civil War: A Narrative, who gives tremendous insights into how Davis and other Confederate leaders truly viewed their side of the struggle. In Foote’s thorough telling, Davis saw the Confederacy as a “second American Revolution” which would overturn the encroachment of big government that had desecrated America’s founding principles. Much of this likely included states’ rights, individual rights to property, and a decentralized and unobtrusive national government. But rights of property and state sovereignty were inextricably linked to slavery. Moreover, Davis proved hardly committed to limited government when he ran the Confederacy like a dictatorship during the Civil War.

What the Civil War was “really” about, alas, is up to interpretation. Yet this question again brings echoes back to the fundamental dilemma of American history. If all that matters is rational economic interests and class struggles, there is no place for ideals or principles in guiding human affairs. And if there is no place for ideals, what place is there for America, given that America is founded, more than anything else, on ideas?

In our next post, we’ll give a brief overview of the Civil War and its aftermath.