What is Presidential March Madness?

In 2019, I came across the idea of hosting “bracket nights”—creating a single-elimination bracket for any subject matter area and gathering with friends to debate each matchup until one champion remains. Topics could include great scientists, statesmen, foods, amusement park rides, pretty much anything. Alas, the pandemic would scuttle bracket nights, along with most all other social plans.

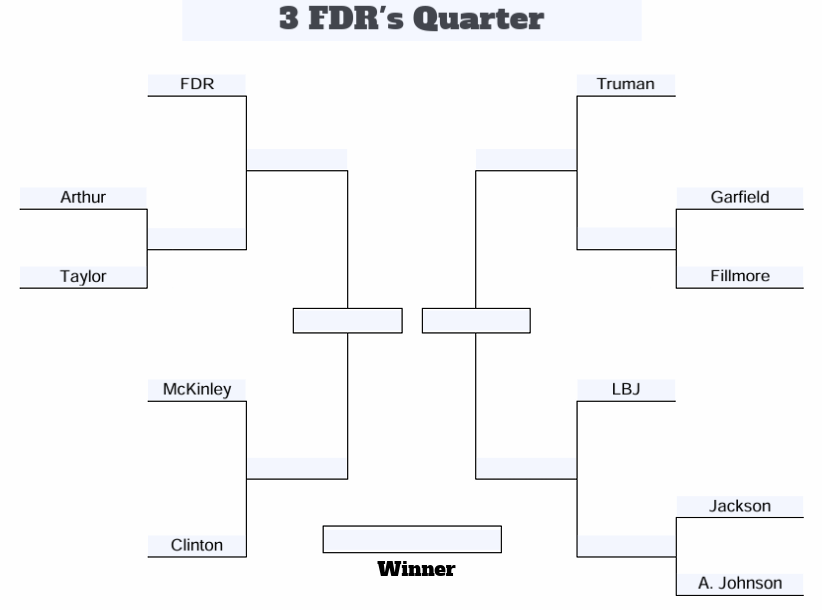

The idea has remained one that greatly intrigues me, and I’ve decided to apply it to former U.S. presidents in a series of posts, in the spirit of the annual March Madness basketball tournaments going on around this time. Here’s how it’ll work.

- I’ll seed all former U.S. presidents in a 44-man bracket, divided into 4 quadrants of 11 each. Note that I’m excluding current president Joe Biden, both to avoid recency bias and to avoid judging him on only a portion of his time in office.

- Seeding will be based on this historical survey from 2021. I’m not endorsing these rankings, but we need a place to start for seeding—upsets can always happen!

- The first four posts in this series will cover one quadrant each, through the round of 16.

- The final post will cover the eight quarterfinalists.

- Each quarter of the bracket will be named for the top-seeded president in that quarter:

- 1: Abraham Lincoln

- 2: George Washington

- 3: Franklin D. Roosevelt

- 4: Theodore Roosevelt

Of course, any exercise like this is highly dependent on what kind of criteria we use. For instance, our authors of Patriot’s and People’s would likely have very different outcomes if they participated. Because of this, I encourage my readers to think through how you would decide each matchup differently, and what criteria you’re implicitly using. And if you differ strongly with any of my conclusions, mention it in the comments.

Here are my criteria, up-front and defined. As always, there’s a tradeoff between thoroughness and clarity. There are seven criteria: whichever president in a single matchup has the better record in four or more will win the matchup.

- Foreign Policy & Crisis Management. This includes actions taken to win or avoid wars, as well as efforts in navigating/preventing emergencies both at home and abroad.

- Consistency with American Ideals & Constitution. This refers, not only to the Constitution itself, but America’s other founding documents (the Declaration and the Federalist Papers, for instance). Part of the executive’s function is to uphold the ideas America is founded on: consent of the governed, equality before the law, and limits of governmental and executive power.

- First Citizenship & Contributions Out of Office. A good president avoids personal misconduct and retains some level of moral legitimacy. Also, a president’s contributions to America (or humanity) either before or after their time in the White House will be considered here.

- Having & Articulating a Vision for America. Another two-part criteria. It is not sufficient to simply have a vision so much as convey one, both to colleagues in government and the American people.

- Contributions to Prosperity. On some level, this encapsulates Reagan’s challenge to Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election: “Are you better off now than four years ago?” Of course, many such factors of well-being are outside presidential control, but the well-being of citizens is an area that governments should be judged upon.

- Minimizing Externalities. Many government actions have long-reaching consequences that will outlive the president who oversees their first implementation. In this category, there are bonus points for leaving the country “better than you found it”, and penalties for leaving a successor stuck holding a ticking time bomb.

- Vice President/Cabinet. I think it’s fitting that in the event of a 3-3 tie in the other six points, the quality of a president’s VP and cabinet should decide the matter. Especially as the executive branch has grown, it’s critical for presidents to surround themselves with conscientious and competent people.

One more procedural note: the numbers next to each president’s name refer to their rankings in the C-Span survey, not their chronological order.

With no further ado—let’s jump into the Madness!

FDR’s Quarter—Play-In Round

(30) Chester Arthur vs. (35) Zachary Taylor

A matchup of two lesser-known presidents. Some history buffs will recognize Taylor as a leading general in the Mexican-American War. He is best known for dying in office a few days after eating cherries and milk at a party, after having served only a year and a half of his term. We’ll make sure not to hold his untimely death against him. As for Arthur, he never won a presidential election, and was thrust into office in 1881 following the assassination of James Garfield.

I give Taylor credit for his military service, adept and bipartisan management of the territorial compromises that Polk’s presidency forced upon him. While Arthur had gained a reputation as an unscrupulous party operative prior to becoming vice president, he supported civil service reform in the Pendleton Act. This was a key step in reducing corruption from both parties.

The matchup comes down in many ways to consistency. Here I give Taylor the edge. It’s not clear-cut, given that Taylor was not a full-blooded abolitionist on the issue of slavery. But he did oppose the expansion of slavery into the new territory conquered from Mexico. In addition, Arthur supported the Chinese Exclusion Act, designed to limit immigration from China—which I consider a blatant inconsistency when contrasted with Taylor’s mixed record.

Final result: Taylor wins, 5-2.

(27) James Garfield vs. (38) Millard Fillmore

In a twist of irony, the next matchup is Garfield (Arthur’s predecessor who died in office) and Fillmore (Taylor’s vice president who succeeded him).

How is such a matchup not a walkover given that Garfield was shot only a few months into his term? Garfield’s win here is solely due to serious bungling on the part of Fillmore. Fillmore’s more radical position on the Compromise of 1850 pushed the south closer to secession. Yet we do give Fillmore some credit for a cabinet that included Daniel Webster and many other leading figures, and his prevention of a more serious north-south crisis. At the end of the day, though: Garfield never had a chance to make the same mistakes Fillmore made, and thus moves on.

Final result: Garfield wins, 5-2.

(22) Andrew Jackson vs. (43) Andrew Johnson

Ah, a battle of two Andrews. Jackson, the “man of the people” who had to flee the White House during his own inaugural celebration. Johnson, Lincoln’s obstinate vice president who managed to antagonize just about everyone following Lincoln’s death.

Jackson’s contributions during the War of 1812 and the general prosperity on his presidential watch earn him a few easy points. But other parts of his record are more subject to criticism. He ignored a Supreme Court ruling regarding the Cherokee people in Georgia—a slap in the face to the principle of independent judicial review. He also endorsed the “spoils system” of government patronage, creating the beginnings of a cycle of expanding bureaucracy and eroding state powers. (Authors of all political stripes criticize different parts of Jackson’s record, as I recount in my “One Country, Two Histories” series.)

On the whole, Jackson is too large an American figure, and Johnson is far too flawed to make this a serious race.

Final result: Jackson wins, 5-2.

FDR’s Quarter—Round of 32

(3) Franklin Roosevelt vs. (35) Zachary Taylor

To me, the high seeds in this quarter of the bracket are all vulnerable to upset—I could see FDR, Truman, and Lyndon Johnson all on upset alerts. I think the way C-Span defines their criteria gives more weight to their achievements than my criteria do.

Despite some of Roosevelt’s weaknesses, Taylor fails to mount a significant challenge. No matter how much credit we give specifically to the New Deal, the economy did improve for the first few years of Roosevelt’s administration. Even if the mini-depression in 1937 was an “externality” of the New Deal, I can’t penalize him for that, as he was still in office. On top of that, he skillfully led the United States through World War II—something that, if anything, my criteria don’t give him enough points for.

Where FDR is vulnerable are his contributions out of office—which can’t match Taylor’s record of Mexican War service—and his consistency with America’s founding ideas. Indeed, much of FDR’s record can be seen as rewriting these ideas, focusing on freedoms from economic hardship as a definition of happiness, and leaving behind the founding idea of each person pursuing happiness as they define it. Because of this idealistic mismatch and his failed scheme to pack the Supreme Court with extra justices, I dock FDR another point. At the end of the day, Taylor isn’t quite able to sniff the upset.

Final result: FDR wins, 5-2.

(6) Harry Truman vs. (27) James Garfield

Now here is the walkover I expected from Garfield earlier. Against a competent president who made major decisions of import and set the tone in U.S. Cold War policy, Garfield simply cannot compete. I do give Garfield a point for externalities, given that Truman left Eisenhower saddled with a war in Korea in 1953. Yet it is far from enough. Garfield is too weak a challenger to even bother with more detail on Truman’s record here—there will be plenty of occasion for that in the next round, I’m sure.

Final result: Truman wins, 6-1.

(11) Lyndon Johnson vs. (22) Andrew Jackson

This one comes down to the wire. Lyndon Johnson was one of the most influential post-World War II presidents, yet his record is vulnerable to criticism on several counts. Jackson’s name defined the era he lived in, yet he too is far from perfect.

Some items are fairly clear-cut. I give Jackson the point for foreign policy in light of Johnson’s prosecution of the Vietnam War. Jackson also gets the citizenship point, again due to his War of 1812 service at the Battle of New Orleans. Meanwhile, Johnson’s vision of a “war on poverty” and the actions he took promoting civil rights for black Americans earn him two points. One could argue that Johnson’s “Great Society” programs went well beyond the scope of the federal government’s enumerated powers. I would tend to consider these programs in a similar vein to the New Deal in their redefinition of the American project’s goal. Yet Johnson’s record on civil rights is good, and Jackson’s defiance toward the Supreme Court seals the consistency point for Johnson.

At a 2-2 tie, the other three points are all more difficult. I give Jackson the point for fewest externalities, considering the economic consequences of war spending and the new welfare programs that Johnson promulgated. I give Johnson the point for a more competent and united cabinet.

This matchup, therefore, swings on the point of contributions to prosperity. Despite the fact that many Johnson-era programs like Medicare are still a feature of our federal government, I give the point to Jackson. Why? I set aside the focus on Johnson’s bold and sweeping domestic policies, and ask a simple question. Were the late 1960s a good time (relative to other times) to live in the United States?

I answer in the negative. People not much younger than me were being drafted for a war the public didn’t completely understand the need for. The convulsions over civil rights, though ultimately fruitful, were difficult and fitful every step of the way. University campuses were overrun with discontented students. It’s fair to suggest that the fiscal combination of Vietnam and aggressive social programs contributed to the inflation that would wreak havoc for over a decade to come (see “externalities”). Because of all this, I give Jackson the point for prosperity, and a narrowest-of-margins upset.

Final result: Jackson wins, 4-3.

(14) William McKinley vs. (19) Bill Clinton

This matchup is close, but feels inevitable. Both have weaknesses, but Clinton’s are simply too much to overcome—although this may say as much about my choice of criteria as it does about Clinton.

McKinley gets credit for his clean personal life, handling of the Spanish-American War, and general consistency of principles. Clinton gets points for mostly avoiding bad things on his watch: a balanced budget, prosperous economy, etc. Given how the rankings play out, I’m surprised that C-Span ranks McKinley higher than Clinton, and would have expected their criteria to reach a different conclusion from mine.

Although at the time many were underwhelmed by them, McKinley’s cabinet picks include names recognizable to us today despite the passage of time. This includes Anti-Trust Act sponsor John Sherman as secretary of state. But above all these towers one figure who has a quarter of this bracket named for him: Teddy Roosevelt. On that alone, McKinley gets the nod over a politically capable but personally “sus” Clinton.

Final result: McKinley wins, 4-3.

FDR’s Quarter—Round of 16

(3) Franklin Roosevelt vs. (14) William McKinley

McKinley is thrust back into action against the top seed in this quarter of the bracket. It’s here, against a president with a more controversial economic record, that McKinley gets a chance to shine.

FDR still gets clear points for foreign policy (World War II) and a vision for America so well-articulated that many of his speeches and policies are still recalled even in basic public school history lessons. After that, McKinley is able to make his moves.

Given FDR’s “pack the court scheme” (and the bold ideological shift the New Deal represented), he loses a point for consistency. He also loses the citizenship point to McKinley’s record of military service during the Civil War. Now at a 2-2 tie, McKinley shows no sign of slowing down. He picks up a point for fewest externalities—which I think is only fair given the far-reaching (and still controversial in some schools of economic thought) consequences of New Deal policies. I also give McKinley the edge in cabinet, again on the strength of Teddy Roosevelt at vice president, and considering that Soviet agents infiltrated many parts of FDR’s administration—including nearly snagging the vice presidency.

By the time we get to prosperity, the matchup is already decided. Here, I again give the point to McKinley, solely on the basis of the general prosperity and avoidance of a significant downturn under his leadership—whereas FDR’s economy had slowed into recession again in 1937. The end result? A giant has fallen!

Note: we’ll still refer to this part of the bracket as FDR’s Quarter.

Final result: McKinley wins, 5-2.

(6) Harry Truman vs. (22) Andrew Jackson

Several years ago I read David McCullough’s outstanding biography of Harry Truman. I remember coming away impressed at his down-to-earth, hard-nosed approach and have considered him often an underrated president. But top six? I’m not sure.

Yet he remains too strong for Jackson to take down. If anything, my evaluation here makes it closer than it should be. Jackson clearly gets credit for his war service, while Truman clearly gets credit for his foreign policy decision-making, more cohesive cabinet, and vision. By the time we get to prosperity and externalities, Jackson is already out of the running. I do still give him the points for each, since Truman left Korea’s resolution to Eisenhower and also attempted to draft striking railroad workers into the Army in order to break the strike—hardly a sound and judicious economic policy.

Final result: Truman wins, 4-3.

Quarterfinalists in FDR’s Quarter:

- (14) William McKinley

- (6) Harry Truman

Join us again next week for more presidential madness!