This article was written on October 30th, 2023. Since that date, new developments in the war between Israel and Hamas may have rendered some facts irrelevant.

“Those who cannot remember the past, are condemned to repeat it.” –George Santayana

On October 7th, Hamas forces (Hamas is the governing party in the Gaza Strip, a 25-mile-long strip of land on the southeastern coast of the Mediterranean) launched an attack on Israel using both rockets and combat militias. The response of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu was to declare formal war on Hamas. The conflict has claim tens of thousands of casualties, with civilians on both sides caught in the crossfire—despite Israeli warnings for civilians to evacuate from the northern part of the Strip. The Gaza Strip is home to over 2 million Palestinians.

Since the 1940s, the dispute between the Israeli state and the various parties that have spoken for the Palestinians displaced by that state has been intractable and prone to moralizing oversimplifications. For its part, American foreign policy has long included support for Israel—at the cost of antipathy from some Arab nations. Indeed, this is one of few areas that leading political figures in the two major parties can agree on. President Biden has already been to Israel since the attacks, and Republican presidential hopefuls like Nikki Haley have referred to Israel as the “first line of defense against Iran”. However, much of Biden’s speech advocated for a “two-state solution”, and he focused heavily on providing humanitarian aid for civilians on both sides of the Israel-Gaza border. While a noble cause, this is a more neutral action than the active shipment of war equipment to Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. This moderation is just enough to leave both parties frustrated. On one hand, the call for a two-state solution (in which Israel and Palestine would carve out separate states for their respective peoples) and a failure to condemn the violence as an unprovoked attack on Israel likely frustrate the Israelis. On the other, pro-Palestinian partisans can point to $3.8 billion dollars in U.S. military aid to Israel in the past year, suggesting that, behind the posturing, American policy may not have changed from that of the 1970s.

As always, the fringes of public opinion are frayed and disparate. American progressives (and their ideological brethren abroad) have grown more vocal in their support of Palestine, largely due to the Israeli-imposed blockade that leads the Gaza Strip to be described as an “open-air prison”. Across the political spectrum, some lament the idea that American taxpayers have funded both sides. Here’s an interesting recent debate that details the intense controversies surrounding the war—as with many controversial issues, the two sides of the argument appear to rely on irreconcilably opposed “facts”.

It’s beyond my knowledge to provide a comprehensive summary of grievances between Israel and Palestine. Instead, we’ll bring a historical perspective to these recent events by discussing a book I’ve already mentioned on my Renaissance Readers’ Library: Years of Upheaval, written in 1982.

Kissinger: Foreign Policy Titan

Henry Kissinger was born in Bavaria, Germany in 1923 to a family of German Jews. At age fifteen, he fled with his family to escape Nazi persecution, and settled in New York City. At twenty, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and won a Bronze Star for his actions in capturing members of the Nazi SS in 1945. Returning from service, he earned three degrees from Harvard (his 400-page undergraduate thesis inspired the introduction of a word-count limit), and remained in academia until the late 1960s.

Despite supporting Nelson Rockefeller’s presidential run in 1968, Kissinger was appointed to serve in Nixon’s new administration the following year, as National Security Advisor, a White House position with direct access to Nixon’s ear. Years of Upheaval was written specifically about the years 1973 and 1974, covering Nixon’s abridged second term. In September of 1973, with Watergate news already breaking across the country, Nixon named Kissinger as Secretary of State.

The first half of Years of Upheaval covers time prior to this appointment, during which Kissinger covers a few key foreign policy topics:

- Negotiating the peace treaty with North Vietnam. One of the few Americans to negotiate directly with Hanoi, Kissinger describes the Vietnamese communists as duplicitous, bent on regional domination, and unafraid to gaslight their American counterparts at every turn in the negotiations. Kissinger unashamedly questions Hanoi’s good faith—and details visits to neighboring Thailand and Laos, who struggled when America’s withdrawals left them on their own.

- Nixon was the first U.S. president to engage directly with communist China, and Kissinger was party to meetings with Chinese leader Mao Zedong and other high-ranking officials as these diplomatic breakthroughs occurred.

- “The Year of Europe”: an effort by Americans to foster more active cooperation on policy between the Americans and the Europeans. Kissinger describes this ambition as the “year that never was”, lamenting the bureaucratic buck-passing and French obstinance that continually thwarted American overtures.

- The fall of the Allende government in Chile, often linked to American covert actions, which Kissinger vehemently denies. It’s difficult for Kissinger to plead ignorance given his encyclopedic grasp of foreign affairs—and the veracity of his claims remains unclear.

- Continuing détente between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Names of Soviet premier Brezhnev, ambassador Dobrynin, and foreign minister Gromyko are peppered throughout the entire book. All of the foreign policy issues above were ultimately viewed through this lens.

Throughout the book, Kissinger weaves two observations about Nixon together. One—Nixon as an advocate of “creative” foreign policy, one which sought to unite America’s friends and divide her enemies. Kissinger praises Nixon for his open-minded approach to global affairs, and mentions him in another of his books, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy. Two—Nixon as a faltering and insecure domestic politician who failed set clear boundaries with his own subordinates, eventually leading to the Watergate break-in. Kissinger places little blame for the scandal on Nixon personally.

The Middle East Erupts

Just weeks into his tenure as Secretary of State, Kissinger had to face another war over Israel. Since the Six-Day War in 1967, in which Israeli air power had routed a coalition of opposing nations, Israel had captured the Golan Heights from Syria (to its northeast) the West Bank from Jordan (to its east), and the Sinai Peninsula (to the southwest). Israeli and Egyptian troops faced each other across the Suez Canal.

On October 6th, 1973, Egyptian and Syrian troops launched attacks on their respective fronts. In Kissinger’s telling, the move surprised the Israelis, the Americans (including himself), and the Soviets. Egypt was a significant power in the region, a leading voice in the Arab League, and had a history of alignment with Moscow. The war would come to be known as the Yom Kippur War, after the Jewish holy day on which the attacks were launched—a parallel that Hamas was no doubt aware of fifty years later.

The Egyptian government reached out directly to the Americans on the second day of the war, in what Kissinger called a “friendly” tone, insisting that Israeli withdrawal from all occupied territories was a prerequisite for peace talks to begin. Yet Kissinger described these terms as “clearly only an opening position”, an opportunity for a delicate diplomatic balance that could be struck.

Israeli troops quickly recovered on the ground, driving Syrians back on October 11th, but the Soviets were ramping up their aid to the Arab nations, while the Americans airlifted equipment to the Israelis. Israeli troops fought back the Egyptians and established a position on the west bank of the Suez, encircling a large Egyptian force in the Sinai. The Soviets implied their preparation for direct intervention in the war, to which Kissinger responded by placing all U.S. forces on heightened alert. In his telling, this caused the Soviets to back down, and a cease-fire went into effect on October 25th.

Shuttle Diplomacy

There remained “a good deal of high explosive lying around” even after the fighting ended. Egypt’s Third Army was trapped in the Sinai, the Soviets felt slighted by America’s initiative in the peace process, and the Arab nations had hit the U.S. with an oil embargo.

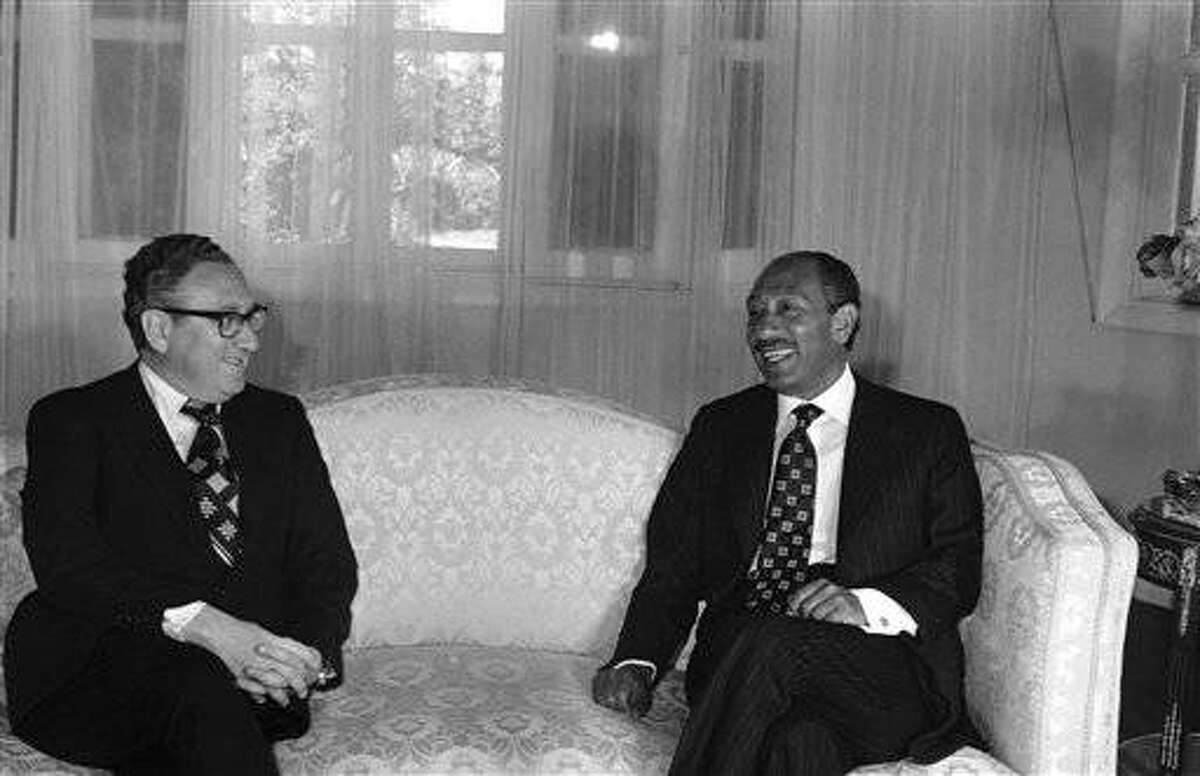

The remaining task was an elaborate four-person diplomatic maneuver involving Egypt’s president Anwar Sadat, Israeli prime minister Golda Meir, Syrian president Hafez al-Asad, and Kissinger. The Soviets were largely left out of the process—included at the formal peace table, sure, but not in the actual negotiations. This was because the negotiations did not take place in a single place—instead, for six months, the negotiations occurred wherever Henry Kissinger was.

“Shuttle” diplomacy was a series of round-the-clock flights taken by Kissinger between Cairo, Tel Aviv and Damascus. For most of this period, Kissinger was the sole intermediary between belligerents that had no tradition of diplomacy with each other.

The Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, approached the peace settlement with grim determination. Through twenty-five years, Israel had been always surrounded by enemies, with friends only at great distance. From this lens (and the lens of the previous two thousand years), even the smallest indication of weakness was an existential threat to Israel. Meir was further hampered by factional Israeli politics, with domestic elections and cabinet intrigues dictating the timetable of peace negotiations in a few cases.

Turning the Tables in Egypt

The first progress came with Egypt. Then-president of Egypt Anwar Sadat also makes the list in Leadership, and Kissinger praises him as a visionary who sought to use war as a means toward a lasting and respectable peace for Egypt following the humiliation of the 1948 and 1967 wars. The armistice centered around mundane issues such as how many artillery pieces, tanks, and other war machines each side could have near the demarcation line, and at what distances. Also at issue was the continued supply of food and medical supplies to the Third Army, trapped behind Israeli lines. Egypt and Israel agreed to a demilitarized zone under United Nations control as their respective forces disengaged, from which point a broader settlement could be considered.

Kissinger does not downplay the impact of Sadat’s efforts. By casting his lot in the diplomacy, he was executing an about-face from Egyptian alignment with Russia and condemnation of Israel. To other Arab nations this was a betrayal, and Egypt was banned from the Arab League for a decade following the Camp David Accords which Sadat would sign in 1979, which normalized peace and diplomatic relations with Israel, as well as returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt. His efforts having antagonized radicals in his own country, Sadat was assassinated on the eighth anniversary of the war in 1981.

Syria: Agreeing to Disagree

The original disengagement between Egypt and Israel brought the diplomatic focus to Syria. Like many in the Arab world, Syrian leader Hafez al-Asad felt betrayed by Sadat’s treating with Israel, but Egyptian-Israeli progress had brought some hope in Damascus. Kissinger attributes this “party because Sadat’s gamble had in fact worked,” that the Syrians were “clearly willing to negotiate, indeed afraid to be left out.”

In the brief war, Israeli forces had occupied more Syrian territory, and the cease-fire line was within thirty miles of the Syrian capital. While the undertaking of negotiations required leaps of faith on both sides, it’s clear that Kissinger saw far greater mutual distrust between Syria and Israel. Much of the negotiation “took the form of an endless series of haggles,” but Kissinger cites that the fragile peace held despite subsequent crises in Lebanon.

Syria and Israel only agreed to disengage their forces, not to settle the border dispute or formally conclude peace terms. Yet it still represented, to Kissinger, a major political achievement: “If radical Syria could sign an agreement with Israel, there were no ideological obstacles to peace talks with any other Arab state.” Further, the conclusion of the diplomacy was a reduced Soviet role in the Middle East. As Kissinger concluded his chapter on the Syrian shuttle: “Thus, the Syrian shuttle seemed to us the watershed between the world of crisis ushered in by the October war and the world of peace toward which we were striving.”

Why This Matters

Based on the above, I will not claim that the Israel-Hamas war in 2023 is analogous to the Yom Kippur War point-for-point. Yet I will mention a few takeaways that can help us understand Middle East conflicts and diplomacy more generally.

Thoughtful and skillful diplomacy matters. This is ever more difficult in the age of social media, which exacerbates the consequences of human tendencies toward indiscretion. Off-the-cuff tweets can create serious misunderstandings in areas where common ground is already so hard to find. Kissinger negotiated settlements between longstanding enemies by seeking to understand each of his interlocutors, avoiding revealing public statements, and treating both sides with honesty about what negotiation could reasonably achieve.

It’s fair to ask whether American diplomatic efforts may be significantly more distracted in 2023, given the Russia-Ukraine war, rising tensions with China, an economy plagued by inflation, and a particularly divided public. These are all fair questions, to which I can only answer with the following: how distracted was the America of 1973-74, with soaring oil prices, double-digit inflation, renewed aggression in Vietnam (after we left), interminable Cold War tensions with Russia, and a nation reeling from war weariness, student demonstrations, and the constitutional crisis of Watergate? Problems and issues have never come one-by-one, and never will.

Negotiations in 1973 were mired in details, just as the battlefield was near stalemate. This is not something America has natural experience with—America’s largest wars (World War 2 and the Civil War tower above the rest) ended with decisive victories and unconditional surrenders. Nor has America ever had to trust its diplomacy to greater powers—the nearest thing in her history was relying on French aid in the Revolution. Further, America’s youth in the family of nations and her idealistic attitudes toward government and foreign affairs make it difficult for Americans to identify with the sort of realpolitik that Sadat, Asad, and Meir saw as a means of national survival. In this setting, negotiating is a game of inches—every hill and town becomes something to haggle over.

More stark are the ways in which the 1973 and 2023 conflicts are different. Here are a few.

- The 1973 war was between Israeli and two other internationally recognized nations. First and foremost, it was a territorial dispute. Egypt sought and regained the Sinai, while Syria sought the Golan Heights. The question of Palestinian statehood is hardly addressed in Kissinger’s account of the negotiations. By contrast, the 2023 war is between Israel and elements like Hamas that claim spokesmanship for the Palestinians. This may make negotiation even more difficult, as each side is more likely to view the other as an existential threat.

- Egypt and Syria had broad support across the Arab world for their war effort in 1973. Jordan, Iraq, Libya, Algeria, and Saudi Arabia all sympathized with Egypt and Syria. Iran, at the time, was the “eastern anchor of our Mideast policy,” as Kissinger put it. Since then, the 1979 revolution in Iran produced a state more hostile to the U.S. and to Israel. Indeed, most of America’s challenges in the Middle East in the last few years have emanated from Tehran.

- The bulk of fighting in 1973 took place in rural areas, relatively far from major population centers. By contrast, fighting between Israel and Hamas is taking place in the densely-populated Gaza Strip, placing civilians squarely in the crossfire.

- While America is still an ally of Israel, the pro-Palestinian voices at home have grown louder in recent years. It’s unclear as yet how this will affect American foreign policy in dealing with the evolving conflict.

Even while American pundits debate the proper actions we should take in response, the United States has surely been working around the clock to find an acceptable resolution—Kissinger’s experience of sleepless nights, constant flights, and midnight meetings is evidence of that. We can hope for a swift end to the violence, an end brokered by diplomacy rather than conquest, and a peace that proves durable for another fifty years and beyond.