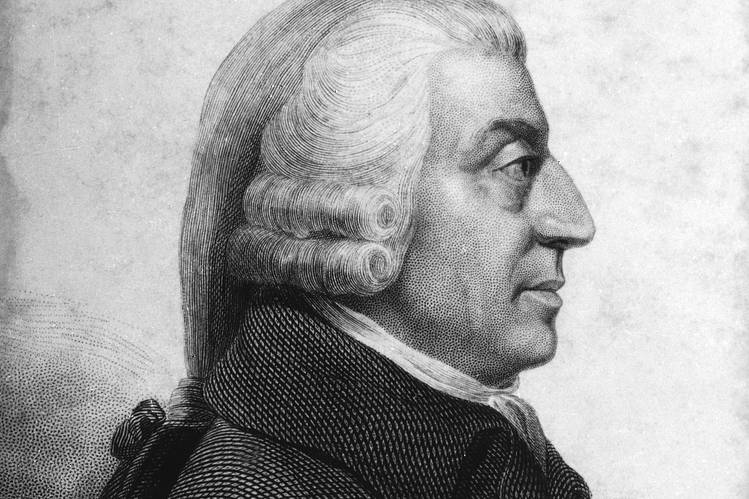

We are back, and excited to bring you our latest series, long in the works: a summary of major works from some of the most well-known economic thinkers in history: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, J.M. Keynes, and F.A. Hayek. In this post, we’re breaking down Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Scotland’s greatest Enlightenment thinker published this work originally in 1776. It has long been referred to as the first promulgator of capitalism and free-market doctrines—but a careful reading suggests that Smith hardly had in mind the creation of any new economic “system” or framework when he wrote. The actual word “capitalism” does not appear in the book. It would be up to Marx, Engels, and others of the 19th century to give a system-like name to this decidedly un-systematic set of ideas—thus capitalism was christened by its opponents.

Capitalism is simply a web of markets, incentives, producers, consumers, prices, and the resulting outcomes, all of which appear naturally in beings with our human natures. To Smith, economics was not a science of postulating formulae or functions, but one of observing incentives. Amid the titans of economic thought, Smith requires by far the least recourse to jargon, and draws the most support from experience and good sense.

For this reason, The Wealth of Nations, though difficult to read—working vocabularies have diminished and definitions have shifted in the past 250 years—is easy to intuitively understand. His book says few new things, and spends a great deal of time linking simple concepts to a plethora of real-world examples. What frameworks he does leave for us are among the simplest and most comprehensible ever devised in his field.

Where Smith does indulge our modern appetite for “-isms” of all kinds is in Volume 4, where he discusses the prevailing idea of political economy—which he describes as the “Commercial” or “Mercantile” system. To Smith, this approach appeared misguided and self-defeating. Thus his only mentions of broad schools of political economic thought are made to criticize those schools—and everything Smith suggests in their place is from a bedrock of first principles.

Readers can expect a post longer than our typical fare, given the length of the work and the depth of insights to cover. In the words of Smith himself: “I am always willing to run some hazard of being tedious, in order to be sure that I am perspicuous [ironically, this hard-to-understand word means “well-understood”].” We will take the same approach. That being said, I assure you that this summary will be a quicker read than Smith’s entire work.

Who Does What, And For Whom?

It Takes All Kinds to Make the World Go ‘Round

Volume 1: Of the Causes of Improvement in the Productive Powers of Labor, and of the Order According to Which its Produce is Naturally Distributed Among the Different Rankes [sic] of the People.

Smith opens the body of his work with a description of the division of labor as a key contributor to improvements in productivity. His case in point: pin-making, in which ten workers can split the “trifling manufacture” into eighteen steps, and by dividing and conquering, they make 48,000 pins in a single day, compared to the 20 they each would have made before—a 240-fold increase in productivity.

He gives little mention to the tedium of such a workflow, but does suggest that agriculture is less given to such divisions of labor than is manufacturing, as “the ploughman, the harrower, the sower…and the reader…are often the same [person].” By this same token, he mentions that “the most opulent nations generally excel all their neighbors in agriculture as well as in manufactures; but they are commonly more distinguished by their superiority in the latter than in the former.” Thus he hints at the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage. Germany can be said to have absolute advantage over Brazil, for instance, in both agriculture and manufacturing, but Brazil likely retains a comparative advantage in agriculture, because the opportunity cost to Brazil of engaging in agriculture is lower (in terms of foregone industrial output) than it is in Germany. For now, Smith merely implies this.

Divisions of labor are both accomplished by and contribute to three aspects:

- Skill of the worker. Making a worker’s task as simple as possible and making this “the sole employment of his life…necessarily increases very much the dexterity of the workman.”

- Focus of the worker. “A man commonly saunters a little in turning his hand from one sort of employment to another,” a habit which “renders him almost always slothful and lazy.” A more specialized labor force thus saves time otherwise lost in moving from one task to another.

- Invention of machines. Machines both create new specialties and are created by them. Smith found it natural that “someone…employed in each particular branch of labor should soon find out easier and readier methods of performing their own particular work.” Some of these improvements can be credited to the “ingenuity of the makers of the machines, when to make them became the business of a peculiar trade,” or even “those…called philosophers…whose trade it is not to do anything, but to observe everything, and who…are often capable of combination together the powers of the most distant and dissimilar objects in the progress of society.”

In a “well-governed society”, the benefits of such division of labor accrue to all people in that society. Without this division of labor, modern economies fall apart simply due to their complexity. Smith mentions a woolen coat (Marx also had a thing for using coats in his examples, suggesting that many economics writers may not have been able to afford fireplaces) as a simple yet compelling example. He mentions ten separate professions involved in the making of such a coat, to say nothing of ship-builders, sailors, wheelwrights, or other industries needed to enable the coat to reach distant markets. He takes it even further: what about the mining and logging needed to supply the ship-builders? The sum of it all: “without the assistance and co-operating of many thousands, the very meanest person in a civilized country could not be provided [for].”

Smith’s comfort with this complexity hearkens to the “stages of production” arguments later advanced by Hayek (which we’ll also cover in this series), and in a sense is a challenge to any “aggregate” measures of economic activity. These aggregate measures have nevertheless found a place in conventional macroeconomic thinking—owing largely to Keynes, also on our docket. I imagine Smith would have admired Hayek, but would likely have found Hayek’s works dense. As for Keynes—I suppose Smith would have found his arguments abstract and ultimately flimsy. But as we work through the works of these other economic superstars, the readers may decide such things for themselves.

In the Beginning, There Was Barter

Division of labor is but the “consequence of a certain propensity in human nature…to truck, barter, an exchange one thing for another.” This began with individuals specializing in work they took naturally to, and evolved slowly until people depended for their livelihoods on “the co-operation and assistance of great multitudes.” Differences in natural talents are in part a cause of division of labor, but are even more so an effect of that division of labor. Humanity alone is a species of specialists which collectively has use for all these specialties.

Logistics is Everything

Market size is a key determinant of the extent of division of labor. “When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment.” Indeed, some industries “can be carried on nowhere but in a great town.” Thus, cities play a role in providing larger local markets for division of labor.

Transportation likewise joins markets into a more unified whole. In Smith’s day, this meant a comparison between water transport and land transport. In our day it means a world of container ships, express air freight, and railroads. Smith’ cites a 50-to-1 efficiency advantage of water transport vs. land transport between London and Edinburgh—imagine what he would think of modern transportation technologies.

Until the railroads, sea freight reigned supreme, and Smith cites the advantages this bequeathed to a number of civilizations:

- Egypt: the internal navigation of the Nile and its canals

- Bengal: likewise with the Ganges

- China: the Yangtze and Yellow rivers.

Left out of these natural highways were the peoples of Russia: “modern Tartary and Siberia” and Africa. In the cold north, the great rivers emptied into the frozen Arctic. In Africa, a lack of natural harbors and great distance between the major rivers discouraged inland navigation.

Facilitating Exchange

Original Money

Smith realized that a system of direct exchange would break down if one party had no item desired by his counterparty. To enable a transaction to nevertheless take place would require “a certain quantity of someone [sic] commodity or other, such as he imagined few people would be likely to refuse in exchange for the produce of their industry.” In other words: something that the counterparty could later exchange for something they did require. This was original money.

The commodity most often chosen was metal. Metals are fungible in the sense that they can “be divided into any number of parts [and]…those parts can easily be re-united again.” Even better, they aren’t perishable. In Sparta it was iron; in Rome, copper; in the nations of Smith’s Europe, gold and silver.

Money Scams: They’re Everywhere!

A key shortcoming of metal as a money item is that it is prone to fraud, where people “instead of a pound weight of pure silver…might receive…an adulterated composition of the coarsest and cheapest materials, which had, however, in their outward appearance, been made to resemble [silver].” The solution to this was coined money, where a verifying stamp would be affixed on the metal, usually by a sovereign.

Yet as soon as the instruments of verifying coinage values were firmly in sovereign hands, they became misused. “In every country of the world, I believe, the avarice and injustice of princes and sovereign states…have by degrees diminished the real quantity of metal, which had been originally contained in their coins.” Smith recognizes such action stands to benefit debtors—including such governments as undertake these steps. Even off the gold standard, the steady inflating away of massive government debts hearken back to a long tradition of state-sponsored financial fraud.

Real and Nominal Values

Given that sovereigns have this interest to depreciate currencies, some truer measure of value must surely be found. To Smith, this is labor. “The value of any commodity…is equal to the quantity of labor which it enables him to purchase or command. Labor, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities.” Indeed, Smith underscores this point several times over. This hearkens back to Locke’s argument that labor is the source of value.

Thus labor forms the “real” value of things, and money forms the “nominal” value of things, which is far more intelligible for day-to-day use than real prices. In another sense, labor can also be said to have real and nominal values: a real value based upon purchasing power, and a nominal value based upon a money wage. This is because the value of labor can change from the perspective of the employer (or purchaser of labor), and labor markets are dictated by the according supply and demand.

As a comparison, Smith cites long-term rents based on quantities of corn, which held their value over the years far better than comparable rents in currency. Non-money commodities are more volatile in the short term: price spikes of grain based on poor harvests, oil supply shocks, etc. But in the long run, commodities tend to store value better than currency.

Wages, Profits, and Rents: Oh My!

Evolution of Labor into Capital

The original state of nature, according to Smith, was one where labor was the only measure of value because labor was the sole owner of all that was produced. Yet this could only last until “stock has accumulated in the hands of particular persons.” The process by which this first occurred is not hard to imagine—for instance, a farmer who through industry, thrift, or fortune, accumulates surplus grain over several harvests, to the point that he has enough to feed someone besides his own family. Thus, accumulated stock is simply the cumulative sum of prior labor.

Note that Smith’s use of the word “stock” is not quite how we employ the word today. He means it more in the form of what we would consider “capital”—any commodity or possession that has value relative to other things.

We can picture a Sumerian farmer hiring a stranger to do the plowing or tend the animals, enabling a more productive farm, and entailing some division of labor. Smith admits that not all owners of surplus would choose to employ it: some might hoard it, others might take their ease and consume it themselves.

Risk and Reward

Smith clearly understood the irrationality of employing stock without some hope of profit by it: “Something must be given for the profits of the undertaker of the work, who hazards his stock in this adventure…The value which the workmen add to the materials, therefore, resolves itself in this case into two parts, of which the one pays their wages, the other the profits of their employer…[emphasis mine]”

Here we have the justification for profit. The hired laborer should not be entitled to the whole fruits of his labor, given that his labor was only made possible by the employer’s decision to risk his accumulated stock. Further, the laborer may have it in his power to kill, rob, or deceive the original farmer—risks which must offer sufficient profits to be worth running. In Smith’s words: “He [the employer] could have no interest to employ them [laborers], unless he expected from the sale of their work something more than what was sufficient to replace his stock…and he could have no interest to employ a great stock rather than a small one, unless his profits were to bear some proportion to the extent of his stock.”

This is the very essence of what Marx describes as creation of “surplus-value”, or the process through which employing capital creates more capital. To Marx, such a process was only possible by exploitation of labor, and had nothing whatsoever to do with compensation for risk borne by employing capital. This is only one area in which Marx makes poor assumptions: we will cover more of them in another post.

This argument rings a bell with the concepts of expected return and risk, which are typically viewed as related to each other. The greater risk a venture poses, the higher should be the expected return on the venture, to compensate for the risk.

Rent: The Profit of Land

I admit it seems strange to me that Smith carves out a third category alongside wages for labor and profits for stock. To Smith, rent is the result of land becoming private property. “The landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce…This portion…constitutes the rent of land.”

Here he risks appearing anachronistic. Wages and profits are intuitive enough, but the setting apart of rents as separate from profits makes less sense…until we realize that Smith’s 18th-century views were less removed from feudalism than we might have assumed. As late as the 17th century, large estates in Britain were held by the landed nobility, most of whom had better things to do than to supervise the management of their land, especially when “better things to do” meant raising private armies, arguing in Parliament, and revolting against the King (the second volume of Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples offers a delightful account of this period).

Interested simply in what they could garner for their holdings, these nobles often became lessors. Still, it is noteworthy that Smith consider this separately from profits—suggesting perhaps that accumulated stock is the sum of prior labor, while distribution of land was largely a function of ancient feudal estates, something given by birth and political fortune rather than industry.

In modern times, rent on land, though less intuitive, still finds some parallels. Take for instance the payments made by energy and mining companies for drilling permits or mining rights—the most basic example is Chevron leasing your backyard to look for oil there. In such a case, you’re entitled to some compensation for allowing Chevron to drill there—even though you probably haven’t a prayer of drilling there yourself.

The Components of Price

Adam Smith was a no-nonsense Scotsman. He gives no place to pretentious formulae. He does not bestow grandiose names on his equations (like Keynes) or devote an entire chapter simply to the exposition of them (like Marx). His explanation of the components of price, to which his entire work so far has built, is scattered across three paragraphs of text.

“In every society, the price of every commodity finally resolves itself into someone [sic] or other, or all of those three parts..[these being] rent, labor, and profit.” Put differently, laborers, employers of stock, and landlords together are entitled to all value produced in a society. Much of the rest of Volume 1 is a series of observations on how this relationship can work in practice, across a variety of cases.

Components of Price in Practice

Stages of Production

The proportion of wages, profits, and rents in goods varies based on many circumstances. In discussing them, Smith offers a harbinger of the “stages of production” concept made famous by Hayek in the 20th century. Rent is a more relevant component of the price of wheat and timber than it is for bread and furniture—it makes sense that greater labor and capital input is required to turn raw materials into finished products. Further, “in the progress of the manufacture, not only the number of profits increases, but every subsequent profit is greater than the foregoing.” This is essentially because the latest stage of production—that is, the one furthest removed from raw material extraction—must generate sufficient profits to repay the cumulative profits of all earlier stages.

Smith stresses that the three components can often be earned by the same person. A small farmer who owns his equipment but not the land he works on should receive both wages and profit for his efforts.

Natural and Market Prices

There are natural rates of wages, profits, and rents, which Smith sees as regulated by “the general circumstances of the society.” In terms of basic economics, we can think of these natural prices as long-term equilibrium prices. In terms of finance jargon, we could consider the “natural profits of stock” as something akin to a cost of capital.

This is all well enough in theory, but in practice, the market price is “the actual price at which any commodity is commonly sold…It may either be above, or below, or exactly the same with its natural price.” This market price is regulated by pure supply and demand. When demand for, say, AI computing chips rises higher than the quantity which NVIDIA can bring to market, some customers “rather than want [lack] it altogether…will be willing to give more.” Thus the price for such chips will rise above the natural price. The opposite occurs when producers bring more to market than the natural demand would bear—and to sell their produce they must “reduce the price of the whole.” All of this should sound familiar to anyone who’s studied economics.

As such, the producer’s interest (whether labor, capital, or landlord) is that “the quantity [brought to market] never should exceed the effectual demand; and it is the interest of all other people that it never should fall short of that demand.”

Such adjustments occur naturally in response to the price mechanism. If demand falls short of supply and the market price of a good falls, sources of supply will be compelled to accept returns (in wages, profits, or rents) below the natural rates. As such, landlords will “withdraw a part of their land”, and laborers and employers will “withdraw a part of their labor or stock, from this employment.” This “exiting of supply” will serve to reduce the output brought to market, supporting the price of the good to rise back toward its natural level. Thus, the natural price is “the central price, to which the prices of all commodities are continually gravitating.” To Smith, the greatest effects of these fluctuations were found upon wages and profits—rents were generally less sensitive given that landlords often secure rents “certain in money,” or at fixed rates.

Permanent Dis-Equilibrium: It’s Possible

When the price of a good rises above its natural price, Smith notes that employers who produce such goods “are generally careful to conceal this change.” If it became common knowledge, the market would become flooded with producers seeking the higher returns, increasing competition and driving the market price (and profits) down. This market inefficiency can’t last long, however, as these secrets are hard to keep.

Technology advantages are generally more sustainable—Smith calls them “secrets in manufacture”. A producer with an improved means of making a good should “with good management, enjoy the advantage of his discovery as long as he lives.” This could likewise apply to all sorts of advantages: a unique business model, a superior strategy, or a differentiated product.

And, of course, monopolies generally evolve into a pricing strategy of “the highest which can be got.” In Smith’s day, monopolies did not spring from anti-competitive business practices (more accurately called “too good at being competitive” business practices), but from government grants, similar to the granting of a garbage collection service monopoly in a given city today.

The three factors above all have the same effect: to prolong or perpetuate a market price in excess of the natural price, thereby enabling producers to capture economic value through returns above the natural rate of return—or shall we say, above their costs of capital. (See our “Good Business” series for a more-detailed breakdown on capital returns vs. capital costs.)

Yet this potential for permanence cuts one way only. “The market price of any particular commodity, though it may continue long above, can seldom continue long below, its natural price.” This is because the same producers/employers of stock who have recourse to gain and defend advantages also have recourse to withdraw their capital from employment in any given industry. This suggests producers perpetually hold an advantageous position relative to consumers: they can walk away from a market more readily, and generally tend to do so, while consumers are often restricted from doing so by necessity or psychology.

Labor Economics and Their Demographic Warnings

Maybe Class Struggle Is Real: Kind Of

In the original state of economy, the produce of labor was itself the price of labor. However, since accumulation of stock and appropriation of land, a portion of that produce must be deducted each for profits to stock and rents to land, as their compensation for making such labor possible. This need not be looked upon as a great loss: returning to a world where labor commands the whole of its produce is akin to taking up hunting and gathering.

Smith admits that in the bargaining contest between laborer and employer, the laborer is continually at a disadvantage. Both have need of the other, but the necessity felt by the laborer is far more immediate. Employers are a less fragmented class, and “are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform, combination, not to raise the wages of labor above their actual rate.” To counter this, Smith claims workers often resort to “the loudest clamor, and sometimes to the most shocking violent and outrage.” One wonders to what extent circumstances have changed since, given universal suffrage and widespread unionization, neither of which were imaginable in Smith’s own day.

Despite any avarice of employers, there is some level below which wages cannot fall: those enough for the subsistence of the laborer. On most occasions, this is insufficient, as the laborer’s wage must be sufficient to provide for a family: a spouse and children who themselves may not work.

Labor, Growth, and the Economist’s Family Planning

The greatest advantage labor can enjoy is its own scarcity or will the demand for labor is “continually increasing.” Smith reiterates again this key point: “It is not…in the richest countries, but…in those which are growing rich the fastest, that the wages of labor are highest.” He cites wages in the American colonies (who were in the process of rebelling) as being consistently higher than those in any part of England, despite the relative wealth of the latter. High wages depend on growth, not on wealth.

Thus there is, in the long run, an equilibrium of supply and demand for labor—that is, for human beings. This plays out, says Smith, in the size of families: “The most decisive mark of the prosperity of any country is the increase of the number of its inhabitants.” And again: in the American colonies, “labor is…so well rewarded, that a numerous family of children, instead of being a burden, is a source of opulence and prosperity to the parents.”

On the other end of the spectrum, Smith cites China: “one of the richest…most industrious, and most populous, countries in the world. It seems, however, to have been long stationary.” He details the awful consequences of this lack of economic growth: “Marriage is encouraged in China, not by the profitableness of children, but by the liberty of destroying them.”

China at least stands still: other places are even less fortunate: places where “the funds destined for the maintenance of labor were sensibly decaying.” He cites as an example the Bengal province of India under control of the East India Company, where “three or four hundred thousand people die of hunger in one year” despite the fertility of the land, largely due to the Company’s incredibly poor governance over the territory.

These are hard sayings for those who grew up reading apocalyptic narratives of the risks of overpopulation. Only recently have a few thinkers (Peter Zeihan comes to mind) sounded alarms over the opposite problem. Perhaps Smith, could he observe the 21st-century world, would examine birthrates and pronounce much of the world stationary—or worse.

In sum: “The liberal reward of labor, therefore, as it is the necessary effect, so it is the natural symptom of increasing national wealth.” Thus, the cycle can be both virtuous and vicious.

Finally, although higher wages tend to increase prices of many goods (as the wage component of these prices increases), this can be mitigated by the employment of the accumulated stock that follows these high wages. This incremental employment can often increase labor productivity while reducing the demand for labor—essentially creating a more capital-intensive economy.

Profits: A Summary

Natural Profits and Rates

The same accumulation of stock (i.e. growth) that raises wages has an adverse effect on profits in any particular industry: “mutual competition naturally tends to lower its profit.”

Smith admits that profits fluctuate far more than wages, to the point that an “average” or “ordinary” profit can be difficult to determine. Yet he offers recourse to common sense: “It may be laid down as a maxim, that wherever a great deal can be made by the use of money, a great deal with commonly be given for the use of it…Accordingly, therefore, as the usual market rate of interest varies in any country, we may be assured that the ordinary profits of stock must vary with it.”

Again, we must bear in mind that Smith’s perspective was far different from our own era of fiat money and central bank-determined interest rates. And we must further consider that Smith defines a relationship between rates of profit and the usual market rates of interest. This suggests a usual, or natural rate of interest, directly related to the natural rate of profit on stock. This idea of a natural interest rate was introduced by Knut Wicksell in 1898, but Smith appears to imply it here.

By this logic, lower interest rates will make the employment of stock more “accessible” by reducing the cost of acquiring it through borrowing. Thus more stock will be employed, although at a lower rate of profit (as expected given the inverse relationship between capital employed and returns on that capital). High interest rates will have the opposite effect: less stock will be employed, but that employed will generate a higher profit.

Well-Governed Society

Recall earlier that Smith mentioned the benefits of division of labor accrue to all assuming a “well-governed society.” As an illustration of why governance matters, he again turns to a discussion of China.

“China seems to have been long stationary, and had, probably, long ago acquired that full complement of riches which is consistent with the nature of its laws and institutions. But this complement may be much inferior to what, with other laws and institutions, the nature of its soil, climate, and situation, might admit of. A country which neglects or despises foreign commerce, and which admits the vessel of foreign nations into one or two of its ports only, cannot transact the same quantity of business which it might do with different laws and institutions. In a country, too, where, though the rich, or the owners of large capitals, enjoy a good deal of security, the poor, or the owners of small capitals, enjoy scarce any, but are liable, under the pretence [sic] of justice, to be pillaged and plundered at any time by the inferior mandarins, the quantity of stock employed in all the different branches of business transacted with it, can never be equal to what the nature and extent of that business might admit.”

Range of Ordinary Profits

Smith describes the lowest ordinary rate of profit as something “more than what is sufficient to compensate…occasional losses.” The highest possible ordinary rate of profit is that which “eats up the whole of what should go to the rent of the land, and leaves only what is sufficient to pay the labor…the bare subsistence of the laborer.” This outlines the range across which profits fluctuate: between the lowest accept premium to take risk and the greatest possible gouging of landlords and laborers.

The Laissez-Faire Fantasy

Given a market without frictions or distorting policies, “where there was perfect liberty”, Smith assumed that “the whole of the advantages and disadvantages of the different employments of labor and stock, must, in the same neighborhood, be either perfectly equal, or continually tending to equality.” This hyper-adaptive market would result from “every man’s interest [which] would prompt him to seek the advantageous, and to shun the disadvantageous employment.”

Yet in the next breath Smith admits this is not true: “Pecuniary wages and profits, indeed, are everywhere in Europe extremely different, according to the different employments of labor and stock.” These discrepancies are partly due to “circumstances in the employments themselves”, and “partly from the policy of Europe, which nowhere leaves things at perfect liberty.”

Some Jobs are More Equal Than Others

Smith lists five aspects of labor that have a reasonable effect on the wages of that labor:

- The conditions of work: whether clean, easy, and honest, or dirty, back-breaking, and frowned upon. More dangerous, difficult, or illegal work should for all these reasons command higher wages.

- The expense of learning the business. A business more difficult or costly to learn should have wages sufficient to recompense “the whole expense of…education…in a reasonable time.”

- The consistency of available work. Smith cites the inability of bricklayers to work during the winter, and that their high wages during the summer months are compensation for “the inconstancy of their employment.” Thus work that is less frequently and reliably available should command higher wages.

- The level of “trust which must be reposed in the workmen.” This results in higher wages for jewelers and physicians.

- The probability of success in that profession. Employments with lower likelihoods of success must offer higher wages to those who do succeed. “In a profession, where twenty fail for one that succeeds, that one ought to gain all that should have been gained by the unsuccessful twenty.”

As an example on the final point, Smith cites lawyers, although I imagine his comments as applying to white collar professions more broadly in our day: “All the most generous and liberal spirits are eager to crowd into them. Two different causes contribute to recommend them. First, the desire of the reputation which attends upon superior excellence in any of them; and, secondly, the natural confidence which every man has, more or less, not only in his own abilities, but in his own good fortune.”

An example I return to on this point is the field of nursing compared with the field of finance. While the mean wage in finance likely exceeds that in nursing, the median wage in nursing likely surpasses that in finance. The probability of success and certainty of employment are far lower in finance, yet the rewards that accrue to the successful are for that very reason all the greater.

The five factors above help to “justify” different financial reward for different professions. However, this can only be done efficiently if the following three factors hold:

- Profession is “well known and long established in the neighborhood.” New professions about which many people know little are not likely to be efficiently “priced” based on their conditions of work.

- Profession must be in its “natural state”, and not subject to any exogenous shocks.

- Profession must be the “principal employment” of its practitioners.

On this last point, Smith expounds on the nature of 18th-century side hustles, suggesting that a worker with extra time “is often willing to work at another [job] for less wages than would other suit the nature of the employment.” But this practice is generally uncommon in rich countries, where most trades are well-established enough to employ a sufficient amount of labor and stock. Indeed, “side hustles” in Smith’s day were found “chiefly in poor countries,” which we must take either as a sign of how much as changed, or a discouraging note on how wealthy the 21st-century truly is.

Overconfidence Bias

Part of this affinity for high-risk, high-reward professions comes from a bias toward overconfidence, which Smith alludes to: “The chance of gain is by every man more or less over-valued, and the chance of loss is by most men under-valued, and by scarce any man, who is in tolerable health and spirits, valued more than it is worth.” While intuitive to some extent, it fails to tie with more recent studies that have suggested loss aversion is a stronger motivator, and people are more apt to over-value risks. This discrepancy may result from our lives today being far more comfortable and convenient than Smith could have imagined.

Lotteries charge a fee for a small chance of great gain. Insurers charge a fee to eliminate a small chance of great loss. Smith cites as evidence for his claim that lotteries are generally oversubscribed, while insurance is often spurned as “many people despise the risk too much to care to pay it.” It’s less clear whether this is true in our own day—although laws such as require car owners to hold insurance have likely distorted the market beyond any possibility of certainty.

The Small-Cap Effect

Smith gives two examples of cases where profits appear incredibly high for businesses where the owner is the sole laborer: a small-scale grocery store and an apothecary. Both these professions require skill, trust, and the employment of modest capital. Because the wages are high, the wage plus profit will appear to result in a high rate of profit given the stock employed—but not all of this is truly profit.

I cannot help but ponder what this means for the returns on capital of small-cap stocks relative to large-cap stocks…but that will have to be a post for another time.

Policy Impacts

A further part of the differences in compensation between employments of labor and stock is found in the policies of Europe, which occasion inequalities “by not leaving things at perfect liberty.” This manifests in three ways.

- By restraining competition to reduce employment in an industry. Governments do this through the privileges of corporations or other sanctioned monopolies. Trade associations (or governments) can further impose requirements for apprenticeships—the original unpaid internships. Yet these arrangements are not necessary, as so many trades “cannot well require more than the lessons of a few weeks,” not years. An apprentice is unpaid, and “likely to be idle…because he has no immediate interest to be otherwise.” Masters gain free labor by apprenticeships, without which they would have to reduce their prices and profits. Thus, like modern unpaid internships, the apprentice system is simply a burdensome tax upon that portion of youth most eager to become industrious. The growth of such systems, to Smith, is partly due to the fact that the industries of a town can combine more easily than most farmers can, simply due to proximity. Yet any such restriction on competition is “without any foundation.” Smith insists: “The real and effectual discipline which is exercised over a workman is not that of his corporation, but that of his customers…An exclusive corporation necessarily weakens the force of this discipline.” Thus: the customer is always right, and business should be accountable to none other.

- By increasing competition to increase employment in an industry. On the flip side are professions that are encouraged through state policies, but are encouraged beyond the point of economic sense. Contributions for education of clergymen, for instance, are so great as to provide education for more people than the Church can ordain—the surplus are what Smith calls “that unprosperous race of men, commonly called men of letters.” Such learned folks eventually become so numerous that the price of their labor grows “very paltry”. Inevitably, they compete with teachers: “The usual recompense of teachers…would undoubtedly be less than it is, if the competition of those yet more indigent men of letters…was not taken out of the market.” Thus, the lower pecuniary rewards for education also harm the pay of teachers. Yet Smith admits this has positive societal consequences: “This inequality is, upon the whole, perhaps rather advantageous than hurtful to the public. It may somewhat degrade the profession of a public teacher, but the cheapness of literary education is surely an advantage which greatly overbalances this trifling inconvenience”—unless you happen to be a teacher.

- By “obstructing the free circulation of labor and stock.” In addition to the complete lack of freedom of many apprentices and other indentured laborers, England historically restricted the movement of the poor throughout the realm. The driving force behind such laws was disagreement about which parish should be responsible for the charity toward the unfortunate. Even beyond this, “particular acts of parliament [sic], however, still attempt sometimes to regulate wages in particular trades and in particular places.”

As Close at Smith Gets to Class Interests

Smith says a great deal about rents, much of which appears no longer relevant given a radically new era of land ownership relative to the 1700s. Yet he does suggest that the rent of land is “naturally the highest which the tenant can afford to pay,” in suggests it is “naturally a monopoly price.”

The closing of Smith’s chapter on rents is particularly noteworthy, however. He observes “that every improvement in the circumstances of the society tends, either directly or indirectly, to raise the real rent of land.” Returning to the three claimants on a company’s produce: labor, stock, and land. Of these, the landed interest “is strictly and inseparably connected with the general interest of the society.” Likewise with the interests of labor: they desire high wages for labor, which, as Smith has illustrated, are a symptom and a cause of growing economies.

It is on the interests of profit that Smith sees far less overlap between the interests of employers and the interests of the society at large. He cites that rates of profit are generally highest in “countries which are going fastest to ruin.” What Marx would call the “capitalist” class understands acutely their own interest. And Smith agrees. “Their [employers’] superiority over the country gentleman is, not so much in their knowledge of the public interest, as in their having a better knowledge of their own interest than he [the gentleman] has of his.”

The final lines of Volume 1 are a harbinger of where capitalism can go wrong:

The proposal of any new law of regulation of commerce which comes from this order [employers of stock], ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

I found Smith’s open admission of this ironic—often credited with the development of “capitalism”, he anticipates Marx’s critique of such a system by over a century—and does so succinctly and without recourse to poor logic. It can all be summed as follows: the system of profit motives is excellent for building an economy in absence of government interference—but such interference on behalf of profiteers is generally damaging to society. Yet the tendency to government intervention is so prevalent—tariffs, subsidies, licenses, regulated monopolies—that Smith’s laissez-faire system indeed has something in common with Marx’s utopia: neither has ever really been tried.

In our next post, we’ll continue our analysis of The Wealth of Nations in discussing capital and how nations develop.