“How do you tell a Communist? Well, it’s someone who reads Marx and Lenin. And how do you tell an anti-Communist? It’s someone who understands Marx and Lenin.” – Ronald Reagan

If we take Reagan’s word for the above, a critical review of Das Kapital must surely place me as a sort of Schrodinger’s communist—I have read Marx, which I claim to understand, but I am firmly not a communist.

My intent to survey a handful of famous economic works has led to months of reading, roughly 2,000 pages of it, with underlining, margin comments, and several iterations of revisiting my notes before finally sitting down to write these overviews. A key takeaway through the entire process has been this: much of economic debate comes down to bickering about different terminologies and frameworks—fitting the “square peg” of one economist’s term into the “round hole” of another writer’s economics framework, for instance—rather than trying to seek a unified set of truths. Apart from Adam Smith, whom we’ve already covered, the economists in our sights write in terms amounting to unpleasant jargon. Hayek did so because he was referring largely to previous economists of the Austrian school, which wrote primarily in German. Keynes did so because he was inventing the “science” of macroeconomics with astonishingly little reference to previous economic writings. And Marx—he did so because he was not really an economist at all.

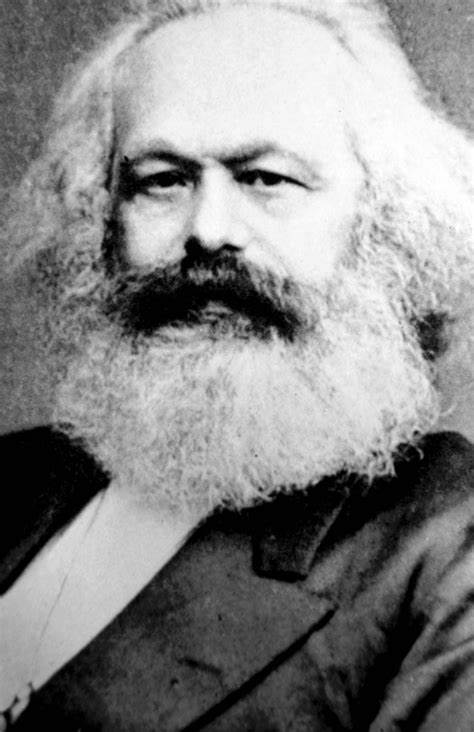

Karl Marx was more properly a philosopher and a sociologist, and his writings tend toward being difficult to understand. It is as if he creates an entirely different language to describe the phenomena he seeks to discuss. He need not plead ignorance: he was clearly familiar enough with at least some of Smith’s writings to cite them in his own. The choice of such convoluted terms as “exchange-value” and “surplus-value” is jarring—perhaps his publisher paid him by the hyphen.

Our analysis of Das Kapital will focus almost exclusively on the first of the three volumes (for reasons I will explain at conclusion). In the printer’s note in my edition, this work “brings forth the inconsistencies in the capitalist mode of production.” Yet much of his central thesis is riddled with unproven priors, illogical if-then statements, and a self-referential air that suggests Marx should have been more concerned with bringing forth the inconsistencies of his pen. We will focus most on his fundamental arguments and assumptions criticizing capitalism, and will explain the fundamental errors of his logic.

I’ll readily admit that I largely read Marx with a strong preexisting bias towards disagreement. The question I asked myself at the start was simple: “Do I disagree with his conclusion, or with his logic?” The answer: I disagree with his logic.

In another sense, what Marx wrote about critiquing the “capitalist” system of political economy was very similar to what Smith wrote a hundred years prior, criticizing the mercantile system. Both made good points about exposing shortcomings of the systems they sought to disparage. Let me say that again: a lot of Marx’s criticisms of capitalism are reasonable, especially when considering that Marx focused far less on pure economic theory than Smith, and far more on political economy. But Marx achieves this not by clever logic, but by simple listing of the abuses and challenges of 19th-century British industrial towns. To arrive at such a conclusion by such a faulty train of reasoning cannot be excused, especially when Smith himself warned against the potential excesses of what Marx would call capitalism:

“The proposal of any new law of regulation of commerce which comes from this order [employers of stock], ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.” –Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Volume 1. Smith clearly knew that “capitalism” was not perfect, and that the merchant and manufacturing classes would seek to wield influence over public policy to favor themselves.

Another old joke about communism is that it works in theory, but not in practice. This is especially ironic given that Marx’s criticism of capitalism is supported by some practical examples (especially at his time and place of writing: late 19th-century Britain) but is founded on incredibly poor theory. And again, many of these practical examples are difficult to dispute, and acknowledged by a wide range of other historians and economists, including Adam Smith.

Thus, where Marx is wrong, he is so spectacularly. And where he is right, he is late to the party. To find out the details, read on. (Note: throughout this piece I will generally revert to the American spelling of words such as labor, criticize, etc. There is only so much that Microsoft Word can tolerate, after all.)

The Semantics of Exchange and Value

“What is a Thing?”

The first few chapters of Das Kapital take nothing for granted. Marx begins with a discussion of commodities, starting with a definition: “A commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another.” (He also describes them as “abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties,” which I consider a candidate for one of the most pretentious sentences ever written.) All commodities have two sources of value: “use value” and “exchange value”. It is exchange-value that renders different commodities comparable, even though this exchange value is not intrinsic to either commodity. One analogy Marx employs is that of the area of a triangle, which “is expressed by something totally different from its visible figure.” When Marx speaks simply of “value” he generally is referring to use-value.

The use-value “has value only because human labor in the abstract has been embodied or materialized in it.” Therefore use-value can be measured by the quantity, or hours, of labor employed in shaping that value.

Yet in describing the “two-fold” nature of the labor power necessary to create such commodities and values, Marx suggests a false equivalency: that “skilled labor counts only as simple labor intensified [emphasis original],” and that the value embodied by commodities takes the form of “identical abstract human labor.” This is the first place in which Marx opts to ignore any concept of human capital.

“What are Two Things?”

Having shown that commodities are both “objects of utility, and…depositories of value,” Marx goes on to provide examples of the relative values of commodities. These are subject to change in value (which we often think of as changes in price—but Marx has yet to deal directly with exchange, and does not yet consider commodities as having markets, only values), or, more accurately, changes in exchange-value, which Marx also calls “relative value”. Part of this is necessary because to be expressed at all, value must be expressed in some understandable form—such as relative to something else, most frequently money. In this sense, Marx describes value as something “purely social”.

Much of Marx’s argument relies on a premise he states simply, one which has implications for how relative value of commodities affects the relative value of the types of labor embedded in them. He asks: “How is the fact to be expressed that weaving creates the value of linen, not by virtue of being weaving, as such, but by reason of its general property of being human labor?” The underlying prior is that all labor must be of equal value, again ignoring skills and human capital concepts. Yet the conclusion of Marx’s reasoning is that the very setting of equivalences between the value of any two commodities through pricing reflects a discrimination between different types of labor.

The First Error: “All Jobs are the Same”

Here we see the first of Marx’s fundamental errors: the assumption that all forms of human labor are “equal and equivalent”. Such a take is disrespectful toward professions requiring years of study and practice to master, such as medicine.

Marx admitted that such detail might appear trivial. Yet he also insists it is critical for a proper understanding of political economy, and even chides Adam Smith for considering “the form of value as a thing of no importance.”

Now We’re Getting Somewhere

The basis of exchange is as follows: “All commodities are non-use-values for their owners, and use-values for their non-owners. Consequently, they must al change hands…Hence commodities must be realized as values before they can be realized as use-values.” Essentially, one man’s exchange-value is another man’s use-value—thus exchange. The universal equivalent to facilitate this exchange would ultimately become money.

That money was metal by nature was clear alike to Marx and others: it could easily be melted together or separately, to isolate any necessary amount for exchange. Such money could in practice be represented by a symbol of itself (such as paper bills backed by gold), although such led to the “mistaken notion, that it [money] is itself a mere symbol.”

Yet despite money playing this critical role as facilitating exchange, “it is not money that renders commodities commensurable.” Indeed, money is merely the measure of the value embodied in the human labor comprising the commodities to which money is applied to measure. This again holds fast to labor as the sole source of value—a concept Smith likewise acknowledged.

Metamorphosis

Marx is an expert at describing things with obfuscating erudition. His concept of the metamorphosis of commodities is the process by which one person sells a commodity for money, and uses the money to acquire a second, different commodity. He denotes this as “Commodity – Money – Commodity”, or “C – M – C”. We can think of the dashes more properly as arrows, but we’ll stick with the dash notation used by Marx. The whole result of this process is simply “C – C”, or “the circulation of materialized social labor.”

Rightly, Marx denies that “every seller brings his buyer to market with him,” and further explains that although “no one can sell unless some one else purchases…no one is forthwith bound the purchase, because he has just sold.” Again, Marx waxes philosophical about the “intrinsic oneness” and “external antithesis” between the acts of buying and selling, but one can infer where he is going with this: that it is possible for a seller to abstain from buying, thus accumulating money and possibly capital.

Here Marx also makes a slight monetary digression: describing the “currency of money” as the “constant and monotonous repetition” of the C – M – C process. Money changes hands twice in this process, while each commodity does so but once. From this he derives a hypothesis from the quantity of money needed “within the sphere of circulation”, and makes appropriate adjustments for how many times each piece of money changes hands (what we would call velocity of money). His conclusion on this score: “the quantity of money functioning as the circulating medium is equal to the sum of the prices of the commodities divided by the number of moves made by coins of the same denomination.” Here he incorporates the time-concept of velocity as well as the quantity of money needed to facilitate a given set of commodity quantities and prices—with the convenient out that any errors could be attributed to money not strictly in circulation.

The Inevitable Accumulations of Money

To hoard money, someone who has just sold a commodity must interrupt the metamorphosis by not selling. In this case, “commodities are thus sold not for the purpose of buying others, but in order to replace their commodity-form by their money-form…and the seller becomes a hoarder of money.” And again: “In order then to be able to buy without selling, he [the original seller] must have sold previously without buying.”

Part of this is of course a greed for exchange-value, which translates into a greed for gold or whatever commodity takes the form of money. But any discrepancies between the timings of a sale and a purchase could also necessitate some money saved up to cover the difference—for instance, getting a paycheck halfway through the month but not spending it all since rent is due on the 1st of the next month.

What Makes Capital Different

General Formula for Capital

As C – M – C represents the successive acts of selling and then buying, M – C – M represents the inverse: buying and then selling. This, however, “would be absurd and without meaning if the intention were to exchange by this means two equal sums of money.”

The proper notation, then, is M – C – M’, where M’ represents a quantity of money greater than the original M. The different between M’ and M is what Marx calls “surplus-value”. This is the “General Formula for Capital”.

The Second Error: Projecting All of Human Greed onto the Rich

Marx calls this formula one of “boundless greed” on the part of the capitalist, whom he describes as a “rational miser”. Yet here Marx appears to apply a double standard. It is fair enough to agree that, as he states, the employment of capital to produce value & profit is indeed a “passionate chase after exchange-value.” But it is, as he said, absurd to assume that a metamorphosis such as M – C – M would have identical start and end values.

The problem however is that in the same way, people equally seek to profit by barter and exchange of commodities even with no intent of making a money profit. In C – M – C, one sells a commodity one does not want, and uses the proceeds to buy a commodity that one does want. The fact that the monetary value is the same does not nullify the fact that the exchange is perceived as a net benefit to the person entering into it—otherwise it would not happen. This subjectivity of use-values would suggest the proper form is therefore C – M – C’, and that by everyday transactions, we all make judgments about what we value and what we do not. How is this pursuit of subjective use-value any less greedy?

One certainly can argue that the subjectivity of use-values that taste can be said to represent makes it incomparable with the more objective pure exchange-value of money—but they are in fact comparable, as illustration can easily show. A house listed for one price can be bid upon at multiple prices, higher or lower than the listed price. Further, an identical house on the same street may be sold for a different price altogether than the first—what therefore is the value of either house? This could be explained by any number of factors extrinsic to the houses themselves: one family liked the style more, the neighborhood more, or was in a hurry to move quickly. These are matters of taste that are subjective and yet move markets. Marx’s framework leaves no room for these, and therefore his premise betrays a poor understand of how markets—any markets—work in practice.

This is Marx’s first error: by labeling values as uniform while vacillating on the duality of use-value and exchange-value (he contradicts himself twice over the course of thirty pages), he paints the “capitalist mode of production”—that is, employing funds at risk for profit—as unique in its manifestation of human selfishness.

Origins of Surplus-Value?

If we assume that the commodity twice changing hands in M – C – M does not change in any form, then it is not possible for the exchange to take the form M – C – M’. Never mind that this insistence of Marx ignores the idea of retail and distribution companies, which indeed can make a profit with remarkably little alteration of their products. Surplus-value therefore cannot come simply from a commodity being bought or sold differently from its true value—any advantage the capitalist could gain on one side of the deal, it would equally lose on the other. “The creation of surplus-value…can consequently be explained neither on the assumption that commodities are sold above their value, nor that they are bought below their value.”

Barring a host of exceptions and near-exceptions (retailing, wholesaling, distribution, and transportation companies, to name a few), we can agree with Marx that surplus-value must be the result of an increase in the value of the commodity before it is sold, an increase brought about by application of labor. As we will find, Marx will have a formula for this: M – C – L – C’ – M’, with the L representing labor power.

“Labor is a Construct”

It’s fair enough that Marx claims the relation between “owners of money or commodities” and “other men possessing nothing but their own labor-power…has no natural basis, neither is its social basis one that is common to all historical periods.” In this relationship, the use-value of labor is advanced to the capitalist, with the laborer often not being paid until a week or two later. (Alas, Marx does not offer a solution to this still-existing problem, and the only proper counter is that the “capitalist” likewise advances funds well before he is able to expect to profit by them—thus capital truly must feel labor’s pain.)

Marx also suggests another concept, one that is of critical importance in understanding his theory. There is some “mass of commodities” which a laborer must be daily furnished with in order to replace the value of his labor to himself. These are commodities such as food, shelter, clothing, furniture, etc. A daily average cost of subsistence can then be computed for the laborer, and an estimate reached of the number of hours of “social” labor (that is, the society’s average labor wage) needed to supply this maintenance. This is the “value” of the labor-power.

Employment is Crime

In his analysis, Marx uses the illustration of a 12-hour day, and refers to a half-day as 6 hours. He also assumes, for illustration, that the subsistence to maintain labor value to the laborer is equivalent to 6 hours of labor.

Here is the rub: “The fact that half a day’s labor is necessary to keep the laborer alive during 24 hours, does not in any way prevent him from working a whole day.” There is the explanation for how surplus-value comes to be: it is exploited out of workers by their employers, who demand more hours of labor than are necessary for the workers, paying them enough for their subsistence and keep the surplus produce of the extra labor time for themselves.

The Third Error: “De Facto Overtime”

Here, Marx treads into even more perilous philosophical ground. He assumes that there is a quantifiable and known “necessary” labor time, based on a quantifiable and known subsistence wage. Further, these arguments in the aggregate do not stand up to examination on the individual level. A worker who can turn the crank twice as fast as another could create twice the value—is this to be dealt with through him working fewer hours at a higher rate for the same total wage, or to be paid more in total?

Even subsistence is not objective: does Marx assume all workers have the same basic diet, the bare minimum of gruel and vegetables? Perhaps some would prefer the occasional steak or salmon, and would be content to toil an extra hour in order to afford them. If so, is the purchase of such luxuries illustrative of non-uniform subsistence wages? Or—even more dangerous for Marx—does it suggest that such luxuries are not subsistence at all, but rather the objects upon which laborers spend their share of surplus-value? One might save up to buy a notebook, a candle, or a fine Sunday suit—but how could anything be saved at all unless those savings were a sum of surplus-values?

One could well rejoin that in many cases, an employer was also a seller of goods, or the only seller of goods, available to workers. It’s certainly conceivable that in such cases as this, any surplus-value the workers could earn is easy prey to above-market prices on all sorts of necessities, through which means their employer steals away their rewards. No doubt this did happen in “company town” arrangements through Britain and the United States. But time—with some help from good old antitrust policies—has rendered this a mere 19th century bug, not an indispensable feature of capitalism.

We have over 150 years of evidence that suggests surplus-value is not uniformly distributed among the “capitalists”. Running water, working indoor toilets, electric lights, telephones, radios, TVs, automobiles, air travel, computers, smartphones—these were either rare or inconceivable in Marx’s day, and are now ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world. Are such items now considered necessities of subsistence? Perish the thought.

Make no mistake: the capitalist class that Marx rebukes certainly got their share of spoils: the fabulous wealth of Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller, and the like. But one cannot demand that any employer of capital advance his funds for the entire surplus value to be enjoyed by others.

Thus Marx’s third fundamental error: the assumption that workers are all underpaid and deprived of any value they generate beyond the bare minimum to maintain themselves. Marx will often recur to this fallacy throughout the rest of his work.

Two Forms of Capital

Like Smith, Marx divides capital into two broad categories. Unlike Smith, Marx bases them upon the capital’s relation to labor. The part of capital that “does not, in the process of production, undergo any quantitative alternation of value,” is constant capital. The part “represented by labor-power” is variable capital. This squares with what Marx has already assumed: that labor is the sole originator of improvements in value.

Although Marx describes capital as “dead labor”, he also explains that “capital did not invent surplus labor”. Indeed, he cites examples of contemporary feudalism in Europe, and could well go further. Thus the class inequalities seem in capitalism are not exclusive to capitalism itself.

The Working Day: Where Marx is Right

In discussion of the working day, Marx displays excellent investigative research. He lists exploitative practices and mistreatments: night shifts, long shifts, health effects on workers, etc. He goes so far as to name specific companies and summarize their failings.

His fundamental point is that the struggle over working hours is a protracted “civil war”, which is one prediction of his that aged fairly well. Accepted norms and legal limits around working hours have continually evolved, largely through labor disputes and strikes. The debates continue today in discussions of a standard four-day work week.

Marx describes surplus-value as consisting of two types. Absolute surplus-value is given by the lengthening of the working day beyond what subsistence labor would require. Relative surplus-value is given by a larger proportion of the working day being given up to surplus-value. For instance, if the “subsistence” level of labor truly has gone from 40 to 32 hours per week, remaining on 40 hours would be an increase in relative surplus-value.

Productivity of Labor

Marx turns from here to discussing changes in productivity. He argues (ridiculously) that a doubling of productivity would not add value, as it would simply result in the value per unit of output falling by 50%. Thus, Marx claims that higher labor productivity reduces the value of labor.

This certainly can be the case if the source of new productivity is an advanced technology or more capital-intensive mode of production, which can produce the same output with more recourse to machines and less to labor. Such would reduce the demand for labor and therefore its value.

But in a case where productivity is the result of improved skill of the laborer, the gains in output in fact increase the value of the labor, as it is that very labor that is necessary to increase productivity. In many ways this recalls Marx’s first error of setting different forms of labor as essentially the same.

Marx on Workplace Culture

It’s difficult to determine just what Marx is trying to say about the importance of cooperation and culture in the workplace. “Each individual laborer, be he Peter or Paul, differs from the average laborer. These individual differences, or ‘errors’ as they are called in mathematics, compensate one another, and vanish, whenever a certain minimum number of workmen are employed together.” This is especially interesting given that he assumes that working in groups will improve productivity: “mere social contact begets in most industries an emulation and a stimulation of the animal spirits that heighten the efficiency of each individual workman.” Marx thus makes clear that group work is more productive than the sum of its parts.

This first assertion of Marx relies on assumptions that don’t always hold: in today’s workplace, office culture and team dynamics indeed play huge roles in productivity, but the sword of teamwork cuts both ways. People often tend to emulate what is around them, and this is not always for good. Instances of organizational cultures contributing to incredibly poor results are not hard to find. (For some of my favorite examples see Michael Lewis’ book on the bureaucratic inertia that jeopardized the U.S. COVID-19 response, or my post on Boeing.)

Setting aside the oversimplification of teamwork’s effects, it remains debatable from whence Marx derives its ameliorative potential. My initial reaction was that Marx was making the point that differences between individuals are not to be preferred, and that the benefit of cooperation consists in their “canceling out”—essentially, that Marx would have cared very little for diversity. But equally the remark could be interpreted the other way, that some diversity is necessary in order to achieve a sufficient “averaging” of labor. We cannot arrive at definite conclusions on what he meant, but his language is strongly suggestive of the former interpretation. One does not refer to individual differences as “errors” without some disregard for them. This speaks volumes about the intellectual hubris of Marx. With over a century of history, with Marxist ideas applied to correcting such individualistic “errors” in Russia, China, Cambodia, Eastern Europe, and beyond, we should not need more examples of what such thinking will entail.

Marx on Division of Labor

Marx acknowledges various ways in which division of labor may occur, but suggests it is an inevitable consequence of the joining of capitalistic production and group work. The final effect of this division of labor is to convert “the laborer into a crippled monstrosity, by forcing his detail dexterity at the expense of a world of productive capabilities and instincts: just as in the States of La Plata they butcher a whole beast for the sake of his hide or his tallow.”

In part, Marx is making a point that Smith seems to omit: division of labor, applied intensively to manufacturing jobs, can result in mind-numbing, tedious work. This was certainly the case in many of the factory environments that Marx would have observed in 19th-century Britain, and can be said to apply to some jobs still today.

But in another sense, Marx’s lament on the wasted potential of the narrow-scope factory worker is inconsistent with his just-stated views on cooperation. It’s difficult to square the requiem for every common man’s “world of productive capabilities and instincts” in nearly the same breath as describing such unique gifts as “errors”.

Yearning for a Simpler Time

In a chapter entitled “Machinery and Modern Industry”, Marx covers several examples of changes wrought in society and economy through capitalist industrial production—all of which he appears to disapprove of:

- Working women and children. To Marx, this had the effects of depreciating the value of labor (by flooding the market with it), increasing infant mortality (due to absent mothers), and generally causing “moral degradation”.

- The capitalist class demanding more intense effort in work, especially when the working day is limited by law.

- The introduction of steam and other sources of power, which would ultimately compete with and seek to replace human labor.

On the other hand, Marx appears sympathetic toward machine-destroying movements such as that of the Luddites, and displays a remarkable nostalgia toward peasantry, referring to it as “that bulwark of the old society”. Late in his life, Hayek wrote extensively in The Fatal Conceit on the tendency of intellectuals to yearn for the primitive state which preceded our own—it appears this is just what Marx is doing. None have grounds to pray a return to yeomanry unless they themselves have wielded a shovel, which Marx did not.

The Reluctant Admission of Rising Wages

As part of the accumulation and growth of capital, Marx admitted that the “growth of capital involves growth of its variable constituent or of the part invested in labor power. A part of the surplus-value turned into additional capital must always be re-transformed into variable capital, or additional labor fund.” The effect of this is that wages will rise as a result of capitalist production. A page on, Marx reiterates this same point, that labor ultimately enjoys an increasing share of surplus-value even under capitalistic production, which “comes back to them in the shape of means of payment, so that they can extend the circle of their enjoyments.”

This reminds me greatly of Howard Zinn’s acidic remark on the grudging admission that America’s prosperous 1920s decade did in fact make many working people better off: “Some farmers made a lot of money.” What neither Marx nor Zinn realized was that this distribution of surplus-value to workers both strengthened the “system” of capitalism and blurred the lines between the capitalist and laboring classes, furnishing each worker with the means to become a capitalist himself, albeit on a smaller scale. This is made especially evident by retirement planning, by which even modest wage earners in the United States can become investors and thus take a seat at the capitalist’s table. Marx fails to realize that this admission in effect can bridge the gap in the class struggle he views as intractable.

The Extras in the Capitalist Movie

In describing capitalism’s effects, Marx hits upon the idea of an “Industrial Reserve Army”: a surplus population made possible only by the increasingly capital-intensive nature of production. To Marx, these extra workers provide “redundant” labor that capitalists can use for taking risks. “Capitalist production can by no means content itself with the quantity of disposable labor power which the natural increase of population yields. It requires for its free play an industrial reserve army independent of these natural limits.”

This does a complete-180 from Smith’s remark that the increase in population is a sure sign of prosperity in any nation. In the same breath, Marx admits that a greater degree of “social wealth” leads to a larger supply of this extra labor. Indeed, Marx both regrets this surplus of human beings and blames it on capitalism. Such distasteful arguments are difficult to morally justify, yet have become increasingly common, partly popularized by books such as Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb. Such arrogant intellectuals never go so far as to express just which people are the “extras” in the human story or just how the problem should be remedied.

It’s possible that this is simply a logical hole that Marx failed to notice, and that he accidentally admits the immense benefits that “capitalism” can have for human prosperity and flourishing. The more sinister interpretation is that he did notice this discrepancy, and determined that the best way to improve the lot of the proletariat was by ensuring great reductions in their numbers—if so, Stalin and Mao can be said to have done their part.

Conclusion: The Sin of Self-Referencing

It is here that we find ourselves at the end of Book 1. My original intent was to write a post on Marx’s entire work, but a full reading of Book 2 changed my mind for a few reasons.

- Books 2 and 3 were edited and compiled by Engels after Marx’s death, which could technically make them not Marx’s work.

- The material in Book 2 is largely borrowed and copied from Book 1, taking many of Marx’s original points and assuming them to be the sole source of truth.

One should clearly see the risks to reason that are posed by any discipline or organization that becomes self-referential. Treating one’s prior work or current thesis as a singular source for truth is the starting point for compounding past errors of judgement into the future. In this sense, Engels seemed to be interpreting Marx as hedge fund legend Ray Dalio interprets his own “Principles”: as a series of undeniable truths which are immune to contrary evidence and through which the rest of the world should be understood. (For a great read on just how hypocritical and self-aggrandizing Dalio’s compendium is, see The Fund by Rob Copeland, an outstanding read.)

This risk of assuming one’s views immune to countering evidence is especially relevant for evaluating Marx’s work and the intellectual revolution that work has wrought across the world. The evidence that Marx worked with at the time of his writing was largely sound—his chapters on specific rules, laws, practices, and abuses are full of detailed examples which we have no evidence to doubt. Marx was right in criticizing the circumstances that he saw. Marx’s positive achievements are those of a “muckraker” journalist: bringing such abuses to light.

But at the same time, his application of that criticism to the prevailing economic order was filled with logical missteps. In my view, he failed to create a coherent framework that could “disprove” the system he intended to dismantle. Hundreds of millions have suffered as a result of these flaws being dismissed or ignored—by Marx himself, by Engels, and later by Lenin and Mao. It is insufficient to pronounce Das Kapital as “bad economics”—it is bad reasoning, bad philosophy, and profoundly bad for humanity.