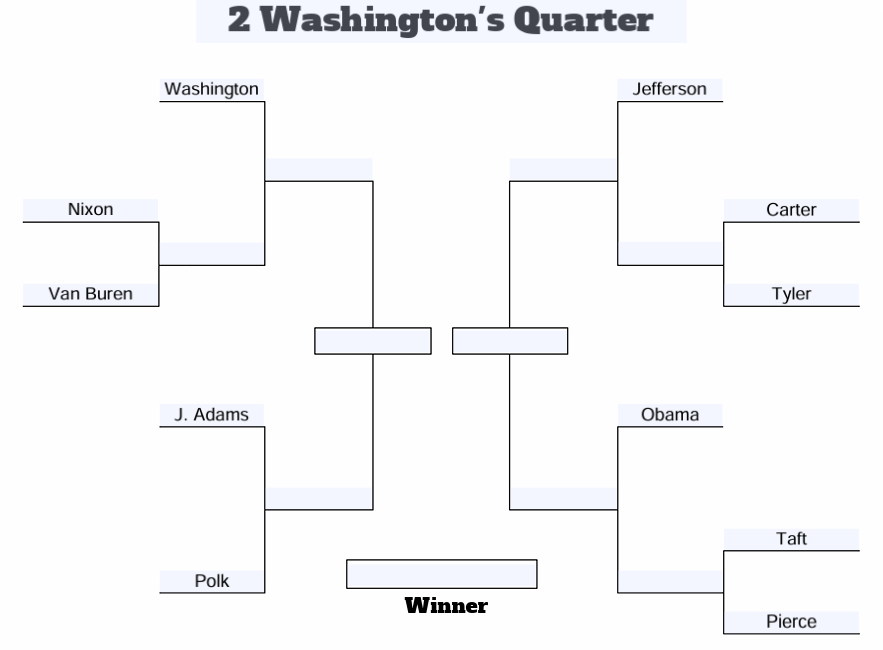

Note: the introduction is the same for each post in this series. Click here to skip to the start of Washington’s Quarter.

What is Presidential March Madness?

In 2019, I came across the idea of hosting “bracket nights”—creating a single-elimination bracket for any subject matter area and gathering with friends to debate each matchup until one champion remains. Topics could include great scientists, statesmen, foods, amusement park rides, pretty much anything. Alas, the pandemic would scuttle bracket nights, along with most all other social plans.

The idea has remained one that greatly intrigues me, and I’ve decided to apply it to former U.S. presidents in a series of posts, in the spirit of the annual March Madness basketball tournaments going on around this time. Here’s how it’ll work.

- I’ll seed all former U.S. presidents in a 44-man bracket, divided into 4 quadrants of 11 each. Note that I’m excluding current president Joe Biden, both to avoid recency bias and to avoid judging him on only a portion of his time in office.

- Seeding will be based on this historical survey from 2021. I’m not endorsing these rankings, but we need a place to start for seeding—upsets can always happen!

- The first four posts in this series will cover one quadrant each, through the round of 16.

- The final post will cover the eight quarterfinalists.

- Each quarter of the bracket will be named for the top-seeded president in that quarter:

- 1: Abraham Lincoln

- 2: George Washington

- 3: Franklin D. Roosevelt

- 4: Theodore Roosevelt

Of course, any exercise like this is highly dependent on what kind of criteria we use. For instance, our authors of Patriot’s and People’s would likely have very different outcomes if they participated. Because of this, I encourage my readers to think through how you would decide each matchup differently, and what criteria you’re implicitly using. And if you differ strongly with any of my conclusions, mention it in the comments.

Here are my criteria, up-front and defined. As always, there’s a tradeoff between thoroughness and clarity. There are seven criteria: whichever president in a single matchup has the better record in four or more will win the matchup.

- Foreign Policy & Crisis Management. This includes actions taken to win or avoid wars, as well as efforts in navigating/preventing emergencies both at home and abroad.

- Consistency with American Ideals & Constitution. This refers, not only to the Constitution itself, but America’s other founding documents (the Declaration and the Federalist Papers, for instance). Part of the executive’s function is to uphold the ideas America is founded on: consent of the governed, equality before the law, and limits of governmental and executive power.

- First Citizenship & Contributions Out of Office. A good president avoids personal misconduct and retains some level of moral legitimacy. Also, a president’s contributions to America (or humanity) either before or after their time in the White House will be considered here.

- Having & Articulating a Vision for America. Another two-part criteria. It is not sufficient to simply have a vision so much as convey one, both to colleagues in government and the American people.

- Contributions to Prosperity. On some level, this encapsulates Reagan’s challenge to Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election: “Are you better off now than four years ago?” Of course, many such factors of well-being are outside presidential control, but the well-being of citizens is an area that governments should be judged upon.

- Minimizing Externalities. Many government actions have long-reaching consequences that will outlive the president who oversees their first implementation. In this category, there are bonus points for leaving the country “better than you found it”, and penalties for leaving a successor stuck holding a ticking time bomb.

- Vice President/Cabinet. I think it’s fitting that in the event of a 3-3 tie in the other six points, the quality of a president’s VP and cabinet should decide the matter. Especially as the executive branch has grown, it’s critical for presidents to surround themselves with conscientious and competent people.

One more procedural note: the numbers next to each president’s name refer to their rankings in the C-Span survey, not their chronological order.

With no further ado—let’s jump into the Madness!

Washington’s Quarter—Play-In Round

(31) Richard Nixon vs. (34) Martin Van Buren

An interesting start in the Washington quarter: two flawed executives who both left last and unsung contributions. Nixon’s: the end of the Vietnam nightmare, improved relations with China, and a peace deal in the Middle East. Van Buren’s: the unstable coalition of the mid-19th-century Democratic party, which failed to head off confrontation between north and south.

This one ends up closer than I’d expected. Nixon wins clearly on three points: foreign policy, vision, and externalities. I don’t consider any of these particularly close. I came away from many of Henry Kissinger’s writings that Nixon was a more savvy foreign policy figure than he often gets credit for. As such, he saw an America that could reclaim a place of strength on the world stage after the failures in Vietnam, and he left the United States in a clearly better foreign policy footing than he inherited from Lyndon Johnson.

However, Nixon is imperiled by two factors: the rampant inflation that his administration failed to address, and (of course) the Watergate scandal. His failed price control schemes give Van Buren a point almost by default. Although Nixon did appoint some cabinet officials of great ability, his White House was full enough of party hacks to enable Watergate to occur. Add on a vice president who resigns in the face of criminal charges, and it’s another point against Nixon.

The race then hinges on idealistic consistency and first citizenship. In hindsight, we can criticize Van Buren’s coalition of northern and southern Democrats as a whistle stop on the inevitable road toward the Civil War. However, at the time he likely considered such a middle ground the best bet to keep the country together—and avoid the hotly contested slavery question. Hindsight will of course condemn him, but he still gets a citizenship point, as Nixon’s reputation has never recovered from the Watergate scandal. On consistency, it’s a close race. But given what America’s founders would likely have thought of Nixon’s links to Watergate, military campaigns in Cambodia, and domestic price controls, I give it to Van Buren. The result is one I didn’t expect.

Final result: Van Buren wins, 4-3.

(26) Jimmy Carter vs. (39) John Tyler

Carter gets his work cut out for him against the forgettable John Tyler. Tyler became president in 1841 following the death of William Henry Harrison. We give Tyler credit for establishing the precedent of the vice president succeeding and finishing out the term following the death of the president. We give Carter credit for his personal honesty, his idealistic foreign policy, and penalize him for the poor economy on his watch.

The only places this matchup feels controversial are in foreign policy and cabinet selections. I give Carter the point in foreign policy despite the embarrassment of American hostages following the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Why? Because Carter also brokered the Camp David Accords, finishing the peace between Israel and Egypt that had started under Nixon. Also, Tyler faced no such similar foreign policy crisis during his term, and it’s unfair to give credit for his “N/A” simply because Carter’s record is mixed.

As far as cabinet goes, neither side is outstanding. But I again give it to Carter, taking into account Tyler’s appointment of leading South Carolinian John C. Calhoun as secretary of state—a pick which strengthened the slavery voices guiding American policy.

Final result: Carter wins, 4-3.

(23) William Howard Taft vs. (42) Franklin Pierce

This one never feels close. In many textbooks, Franklin Pierce is at best ignored. At worst, he is cast as a weak and rudderless executive unfit for the challenges of slavery and sectional politics that led to the Civil War. Against him is Taft, a progressive Republican who also served as chief justice on the Supreme Court.

Perhaps I should give Pierce some credit for assembling a competent cabinet that carried out a few far-reaching policies, including an early stab at civil service reforms and the acquisition of southern Arizona in the Gadsden Purchase. But he was undone by his inability to stall the sectional violence that caused havoc in Kansas during his term, and would eventually cause havoc on battlefields from Gettysburg to Vicksburg. Further, some in Pierce’s south-leaning administration sought to annex Cuba to make more room for slavery to expand—such foreign policy dissention can hardly be a sign of a strong cabinet. The result? Taft is barely tested, and we have our first sweep.

Final result: Taft wins, 7-0.

Washington’s Quarter—Round of 32

(2) George Washington vs. (34) Martin Van Buren

Van Buren simply does not have the record to go toe-to-toe with the “Father of our country”. Old Kinderhook (as Van Buren was nicknamed, leading to the phrase “OK”) was able to get past Nixon because both presidents had flawed records. Washington, however, is virtually unimpeachable.

Washington’s foreign policy, strength in a crisis, and contributions outside the presidency should all be obvious. (His record is especially notable given the string of foreign policy crises he faced, as I mention in my “One Country, Two Histories” series.) He refused the suggestion that he be made king, and his austere modesty did much to preserve the ideas of liberty that America fought for. While his cabinet was wracked by more intrigue and disputes than most others, this was because Washington refused to let party favors stand in the way of including the best and brightest. It was up to Washington to put the Constitution and its framework into practical use. That he did so with restraint and dignity commands our continued gratitude.

Ultimately, Washington was a far more principled and capable statesman and leader than Van Buren, with none of the moral corruptions that made Nixon vulnerable. Another sweep.

Final result: Washington wins, 7-0.

(7) Thomas Jefferson vs. (26) Jimmy Carter

Another titan from Virginia in a matchup that feels unbalanced. However, in this one, Carter has a shot to land some punches.

Jefferson’s vision for America is undeniable: he was in many ways behind the Democratic-Republican concept of a weak central government (especially the executive) and an economy aligned with agriculture rather than manufacturing and finance. America elected three successive Democratic-Republicans to follow Jefferson—testifying clearly to the popularity this vision enjoyed. His contributions to America through the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis & Clark expedition earn their place in America’s early lore. He sent American forces to deal with pirate states in north Africa. His cabinet, though not as nonpartisan as Washington’s remained full of eminent persons, including James Madison.

Yet there are still two weak points in Jefferson’s record. The first is his personal conduct: he fathered children with one of his slaves, yet never setting her free. This looks particularly bad when compared with a president in Carter who generally told the Americans the truth and avoided major personal pitfalls. However, I still give Jefferson the points here solely due to his other contributions outside of the presidency. He wrote the Declaration of Independence, served as ambassador in France during critical parts of the Revolutionary War, and served in high-level posts in the first two administrations (Washington and Adams).

The other weak point is enough to swing a point in Carter’s favor. The Louisiana Purchase and the wars with the Barbary States in Africa may be positives on Jefferson’s record, but they were clearly outside the constitutional bounds of executive power—and especially outside the bounds that Jefferson and other so-called “anti-Federalists” thought were appropriate (as I mention in “One Country, Two Histories”). Because of this, Carter gets a point for idealistic consistency—just enough to avoid getting swept.

Final result: Jefferson wins, 6-1.

(10) Barack Obama vs. (23) William Howard Taft

Similar to Trump’s first-round matchup against Coolidge, this one is difficult to be objective about, given that it pits a very recent president against a much earlier one. I think that relative to my criteria, the C-Span survey’s different focus (they equal-weight 10 different criteria to build their rankings, and also rank the presidents separately on each one) is overrating Obama. Part of this view is shaped by my recollections of Obama’s time in office: a recession that seemed to go on forever, a speech that broke the record for use of the word “crisis”, and a general retreat from global assertiveness and competitiveness that left many feeling frustrated. Against Taft, this is a lot to overcome. Taft’s service on the Supreme Court, his success at combating monopoly powers of business trusts, and his more restrained style of progressivism, give him the upper hand.

However, Obama gets credit for a few things. Despite a failure to come to grips with terrorist groups like ISIS, the U.S. killed Osama bin Laden on Obama’s watch—which is enough to swing the point. A gifted speaker, Obama laid out a clear vision for the country that was inspiring even to those he differed with on policy. He gets credit for his vice president and cabinet mostly because his actions did not bring a major breach of his party, as Taft’s did (with Teddy Roosevelt, Taft’s predecessor).

At the end of it, Taft squeaks by.

Final result: Taft wins, 4-3.

(15) John Adams vs. (18) James Polk

In my view, Adams has the weakest record of the “founding father” presidents. Yet despite his incredible unpopularity in office (he rode in essentially on Washington’s goodwill), he put together some decent achievements. Yet his record is far from perfect, and gives opportunity to Polk, a Tennessean who led America in the Mexican War and oversaw large territorial acquisitions in the aftermath.

Polk gets credit for a far less fractious cabinet that Adams’—partly because Adams was stuck with the presidential runner-up, Jefferson, who disagreed with him about virtually everything. But he loses a point for the re-ignition of the slavery question that the territorial gains from Mexico invited, placing the nation on a slope toward the Compromise of 1850 and Kansas-Nebraska Act (both after Polk’s term). While Polk wasn’t a part of these attempts at a solution, his designs on expansion to the southwest certainly made the problem more difficult for subsequent presidents.

Adams gets clear credit for his citizenship and vision; the state constitution of his native Massachusetts, which he wrote, became a model for those of many other states. I also give Adams credit for crisis management, given that he managed to avoid entanglements in the wars between Britain and France, despite many Americans demanding their country to choose a side. In addition, Adams won election in 1796 under a contested ballot (Georgia, ironically), and took procedural steps to invite any challenge of the election results that would ultimately propel him to office.

A weak point for Adams is consistency with American ideals. This is the most contested point in this matchup, given Adams’ endorsement of the Sedition Act, a clear infringement on American concepts of individual rights. Yet I still give him the point based on Polk’s provocation of war with Mexico for his own party’s political advantage.

Final result: Adams wins, 5-2.

Washington’s Quarter—Round of 16

(2) George Washington vs. (15) John Adams

This is an ironic matchup, given that Washington’s popularity and Federalist leanings helped Adams win election. It is also a highly one-sided affair.

Everything Adams did well—avoiding foreign wars, contributing to America’s victory for independence and post-independence government, articulate and uphold American founding ideals, deal with Thomas Jefferson in cabinet—Washington simply did better. In a matchup where on policy lines there is little to differ on, character and consistency count the most. Washington’s strength of character delayed the partisan infighting that plagued Adams during his term, and Washington’s restraint stands in contrast to the Sedition Act passed under Adams. A tough break for Adams here.

Final result: Washington wins, 7-0.

(7) Thomas Jefferson vs. (23) William Howard Taft

This matchup is closer than the scoreline indicates, and again underscores the difficulty of comparing presidents from such different eras. Jefferson clearly wins points for foreign policy, a vision for America, and an eminent cabinet. Taft gets a point for the trust-busting actions that helped rein in some laissez-faire economic policies of the late 19th century. So that puts us at a 3-1 lead for Jefferson.

And that is where things get tricky. How to balance Jefferson’s overreaches in Louisiana and the Barbary States with the fact that most of Taft’s actions would be considered even more blatant executive measures by the standards of Jefferson’s time? On this point, I give Jefferson the benefit of the doubt.

Not so on first citizenship, though. It’s also a struggle to compare authorship of the Declaration of Independence with distinguished service on the Supreme Court. Yet as a tiebreaker, I fall back on Jefferson’s six children with his slave-mistress, and give Taft the point. On externalities, I’ll give Jefferson the point in light of Taft’s breach with Teddy Roosevelt that handed the White House to Woodrow Wilson in 1912.

Final result: Jefferson wins, 5-2.

Quarterfinalists from Washington’s Quarter:

- (2) George Washington

- (7) Thomas Jefferson

Join us again next week for more presidential madness!