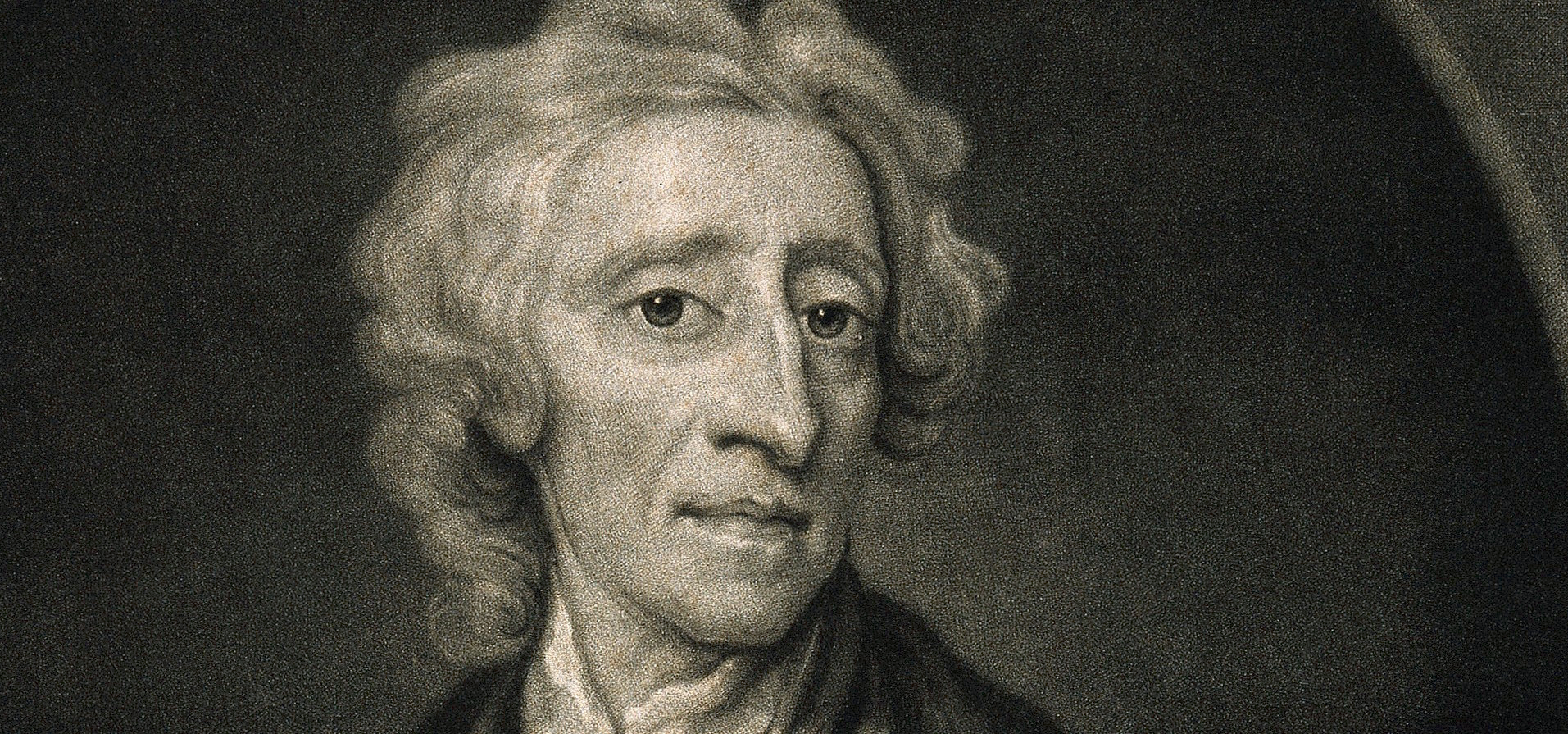

In many high school civics courses (or at least what remain of them), John Locke is usually given a passing credit as one of the political thinkers who did much to shape the ideals expressed in America’s founding documents. Such courses often lump him together with other enlightenment thinkers, including Thomas Hobbes.

Locke and Hobbes were active during the second half of the 17th century, a time in which England saw two revolutions, a decade of parliamentary dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell, and the final deposing of the Stuarts. In essence, the time was ripe for political arguments that were truly radical for their time. We can perhaps get a glimpse into this if we imagined for a moment that, in addition to all the other legal and electoral drama around him, Donald Trump was advocated by some as having a divine right to absolute power, answerable to none but God.

For Locke’s part, he puts forth his views on such subjects in his 1689 Two Treatises of Government. In this work, he stakes out a position far more radical than two earlier works:

- Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) had advocated for absolute monarchy as a product of the social contract between equals. Such an arrangement was justified by the government’s promise of protecting subjects from “fear of violent death”, among other things.

- An even less liberal position was that of Robert Filmer. In 1680, decades after Filmer’s death, his views became known through publication of his Patriarcha. Basing his reasoning on biblical arguments derived heavily from Adam and Eve, he insists that equality among mankind had never existed, and that absolute government therefore could not be a product of any social contract between equal citizens. Instead, absolute government was justified by the divine mandate given to Adam and his heirs at the creation of the world.

The timeline of these writings is especially interesting when considering events in England. Filmer’s work was published in 1680, during the restored rule of the Stuart family on the English throne. Locke’s Two Treatises first appeared in 1689, a year after the “Glorious Revolution” which deposed the Stuarts and placed William and Mary of Orange on the throne with Parliament’s blessing. That Patriarcha was published while the royals sought to subdue a Parliament that had beheaded their predecessor appears not to be a coincidence. (For a fine narrative account of the Stuarts’ spats with Parliament, I refer the interested reader to Churchill’s History of the English Speaking Peoples.)

Therefore, it should not surprise us that Locke’s take was radically different from Patriarcha. Indeed, the entire first treatise in Locke’s work is a point-for-point refutation of Filmer’s arguments. Each work can then be seen as a product of its respective political climate—but to label each merely as such is unfair to Locke. After all, his works are still read and referred to (sometimes erroneously) today. While Filmer sought to defend a dying political tradition, Locke expounded a new one.

In this post, we’ll examine Locke’s positions and their implications in detail.

Some Notes on Style

I find Locke a classic example of English enlightenment writing: structured, logical, essentially a series of if-then statements in virtually impenetrable prose. I contrast this with French thinkers (like Rosseau) who write with far less regard to order of topics or explanation of premises. Locke takes every care to weight arguments as analytically as possible. Even the structure of each treatise, with separate headings for each paragraph, supports this approach.

Throughout the work, Locke universally refers to humankind as “man”, or “men”. However, it should be abundantly clear in the following when he means to refer to all people vs. when he refers strictly to men. I leave the reader to judge whether any confusion shall arise on this front.

Treatise 1: Smashing the Patriarcha

Locke describes Filmer’s two premises: “That all government is absolute monarchy…that no man is born free.” Quoting Filmer directly: “Not only Adam, but the succeeding patriarchs, had, by right of fatherhood, royal authority over their children…Neither common nor statute laws are, or can be, any diminution of that general power, which kings have over their people by right of fatherhood.” Filmer’s basis for this is scriptural, largely based on Genesis 1:28, which states (King James Version) God’s command for Adam to “have dominion…over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

The Grant of Creation

Filmer goes so far as to claim that any supposition of “natural freedom” must necessarily deny the biblical creation story. Yet Locke dismantles Filmer’s argument by a close reading of this same scripture. Referencing other scholars who contended that God’s grant to Adam conveyed property but not political mandate, Locke resolves that this grant was a “right in common with all mankind; so neither was he monarch”. He further references Psalm 8, where King David wrote of God’s grant to mankind as referring to mankind, rather than purely to Adam. And he cites another example from the New Testament in 1st Timothy 6:17: “’God gives us all things richly to enjoy’, which he could not do, if it were all given away already, to Monarch Adam, and the monarchs his heirs and successors.” On these grounds, Locke contests Filmer’s interpretation of monarchical power by creation.

The “Subjection of Eve”

Another of Filmer’s premises is found in Genesis 3:26, in which God tells Eve: “he [Adam] shall rule over thee”. Locke mocks such a claim as evidence of Filmer’s bias: “For let his premises be what they will, this is always the conclusion; let rule, in any text, be but once named, and presently absolute monarchy is by divine right established.”

Locke does not go so far as to deny that God claimed woman to be in subjection to man—and his argument thus limited, he is liable to appear anachronistic to today’s audience. Yet he does point out some incongruities with Filmer’s logic. The words quoted are spoken to Eve by God after Adam and Eve have eaten the forbidden fruit; God’s words to Eve are her punishment. In this sense, they are not a “grant to Adam”, but rather a “punishment laid upon Eve.” As such, Locke reasons it applies to women only, not to men, and thus “if therefore these words give any power to Adam, it can be only a conjugal power, not political; the power that every husband hath to order the things of private concernment in his family”.

Adam himself is not exempt from punishment for original sin. He is sentenced to till the earth for his living, banished for the plenty in the Garden of Eden. This does not escape Locke’s notice: “It would be hard to imagine, that God, in the same breath, should make him [Adam] universal monarch over all mankind, and a day-labourer for his life”.

Fatherhood as Monarchy

The third leg of Filmer’s rickety stool is fatherhood: that Adam and other patriarchs of old had “by right of fatherhood royal authority over their children”. Yet Locke insists that God, not man, is the “author and giver of life”. He rhetorically asks: “What father of a thousand, when he begets a child, thinks father than the satisfying his present appetite?” Further, such a claim to dominion would serve naught but to “give the father but a joint dominion with the mother…for no body can deny but that the woman hat an equal share, if not the greater”.

Locke cites multiple references from Genesis, Matthew, and elsewhere that speak to the unity of man and woman in marriage and parenting. Locke points to the father and the mother “being joined all along in the Old and New Testament where-ever honour or obedience is enjoined children.” Again, this suggests that any parental right of dominion which fathers possess is not solely their own, and thus cannot be the basis for any absolute monarchy.

Parenthood as politics has a further shortcoming: multiple generations. Were one to follow Filmer’s logic, all men with living fathers and living children “are at the same time absolute lords, and yet vassals and slaves”.

“Who Heir?”

Even the strictest biblical scholarship would place the time between Adam and Locke’s day around five or six thousand years. Pointing to the multiplicity of 17th-century monarchs, Locke insists Filmer must prove “that the princes and rulers now on earth are possessed of this power of Adam, by a right way of conveyance derived to them.” If this cannot pass muster, “it will destroy the authority of the present governors…since they, having no better a claim than others to that power, which is alone the fountain of all authority, can have no title to rule”.

Filmer contradicts himself by stating that each “multitude of men” will include “one man…that in nature hath a right to be king…as being the next heir to Adam”. Yet he also suggests that there is only one true heir. Locke insists that “if there be but one heir…there can be but one lawful king in the world, and no body…can be obliged to obedience till it be resolved who that is.” But “if there be more than one heir of Adam, every one is his heir, and so every one has regal power”.

Nor can the issue be referred to the history of the ancient Hebrews, which “had hereditary kingly government amongst them not one third of the time” of the Old Testament.

Having thus dismantled Filmer’s arguments, Locke turns to his second treatise “Of Civil Government”, wherein he describes the state of things as he sees it.

Treatise 2: Locke’s Conceptions of Nature and State

Locke’s state of nature is one of where all people possess “perfect freedom to order their actions…equality…yet it is not a state of license.” None has a right to harm another’s “life, health, liberty, or possessions”, but “every one has a right to punish the transgressors of that law to such a degree, as may hinder its violation”. Thus Locke’s state of nature includes the right to redress wrongs caused by excessive license on the part of others. Such a state of nature ends when men “by their own consents…make themselves members of some politic society”.

In discussing freedom, Locke and Filmer have separate definitions. Filmer defines freedom as freedom from laws, while Locke describes freedom under laws: “freedom of men under government is, to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society…freedom from absolute, arbitrary power”.

Property: What’s “Ours” is “Mine”

In keeping with his line of argument in the first treatise, Locke admits that dominion over earth was given to mankind in common. Yet he suggests that man can still retain private property in the sense as “the labor of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his”. Thus by laboring to gather or obtain the bounty of nature for himself, a man makes that portion thereof his own, and such portion ceases at once to be the common property of all.

He justifies this further by taking a humanist reading of God’s commandment to Adam in Genesis 1:28: in Locke’s words, “to subdue the earth, i.e. improve it for the benefit of life”. He suggests that such appropriations were not “prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough, and as good left”—a condition that can fairly be questioned today.

It’s worth noting that Locke’s claims about labor as “title” to property align with the labor theory of value proposed by such writers as Karl Marx. Given this, it’s interesting to ponder how Locke would have felt about the age of capitalism that arose in the following centuries: would he have espoused a more Marxist favoring of labor? Or would he have taken the Hayekian notion that capital itself is justified property, as it represents a product of earlier labors?

Money and State

Before introducing money (or any means of exchange), Locke suggests that mankind had no yardstick to value any things beyond those necessary to the preservation of one’s life. Yet such exchange “introduced (by consent) larger possessions, and a right to them”. Without this, Locke contends that the old rule would hold, that “every man should have as much as he could make use of”. He suggests therefore that money is a foundation of economic inequalities: “since gold and silver…has its value only from the consent of men…it is plain, that men have agreed to a disproportionate and unequal possession of the earth”.

By organizing themselves into states, men “have, by common consent, given up their pretences [sic] to their natural common right…and so have…settled a property amongst themselves”.

Paternal Power

Locke continues to contend that the power of parenthood is derived from both mother and father. This power “arises from that duty which is incumbent on them, to take care of their offspring”. Yet this commend is temporary. A father cannot command disposition of a child’s life or possessions.

Origins of Civil Society

The first civil society, as Locke describe it, was marriage. Such was a “voluntary compact” that “draws with it mutual support and assistance, and a communion of interests”. From this came the political societies with a similar model. Man relinquished his birthright of “perfect freedom” and, with others, “resigned it up into the hands of the community”.

This consensual act of forgoing preexisting natural rights is the only legitimate foundation for any society or government. Therefore, “absolute monarchy…is indeed inconsistent with civil society, and so can be no form of civil-government at all”. Without a voluntary agreement to enter into a political society, no political society can be said to exist.

By entering into a political society: “every man, by consenting with others to make one body politic under one government, puts himself under an obligation, to every one of that society, to submit to the determination of the majority, and to be concluded by it; or else this original compact…would signify nothing and be no compact…Whosoever therefore out of a state of nature unit into a community, must be understood to give up all the power, necessary to the ends for which they unite into society”.

Locke further stresses the right of men for “withdrawing themselves, and their obedience, from the jurisdiction they were born under…and setting up new governments in other places”.

The chief purposes of government, to Locke, is “preservation…of property”. Such is necessary due to the “corruption and viciousness of degenerate men”. Yet this need not necessarily be a democracy, “but any independent community”, for which Locke uses the phrase “commonwealth”.

Structure and Powers of Government

Legislative power in any commonwealth is “supreme…sacred and unalterable”. It’s sole end is “preservation, and there [it] can never have a right to destroy, enslave, or designedly to impoverish the subjects.” It cannot take property from any man except for each one’s “proportion for the maintenance of it [the government]. But still it must be with his own consent, i.e. the consent of the majority”.

Locke endorses the idea of separation of powers between the legislature and an executive who is responsible for the fulfillment of the laws: “it may be too great a temptation to human frailty…for the same persons, who have the power of making laws, to have also in their hands the power to execute them”. He further justifies a separate executive power by his enumeration of “federative” powers: “the power of war and peace, leagues and alliances”, etc. These federative powers must be placed in one set of hands, as they “require the force of the society for their exercise, and it is almost impracticable to place the force of the commonwealth in distinct, and not subordinate hands”.

While the legislature is supreme, the people are supreme over and above it. Thus Locke creates a hierarchy with the people at the top, the legislature beneath them, and an executive “visibly subordinate” to the legislature.

Locke clearly recognized the tendency to grant “prerogatives” to the executive, things “left to the discretion of him that has the executive power”. Such benefit of the doubt is “always largest in the hands of our wisest and best princes”, yet this creates a danger in the long run. Examples in America can be found among presidents who, through their achievements and abilities, expanding the scope of executive powers far beyond the point which either Locke or the original Constitution outlined. Thus Locke contends that “the reigns of good princes have been always most dangerous to the liberties of their people”, as a good prince is granted prerogatives which devolve upon less able successors.

Locke

“The end of government is the good of mankind.” Such Locke tells us. Thus, summing up his arguments, he opens the door to a political tradition beyond the absolute monarchies the ends of which were the pleasure of the rulers. He forms a philosophical basis from which Thomas Jefferson borrowed heavily in writing the Declaration of Independence, and outlined a simple separation of powers principle well before Montesquieu expounded further on that subject. That such claims were made at the sunset of “divine right” principles in England gives grounds to suggest that Locke gave a voice the political movement of his day, one which would be recognized and fought for in the Americas a few decades later. His Treatises are thus doubly valuable: as a reflection upon the political discourses of the late 17th century, and as a summary of the basic principles upon which the United States was founded.

If you’re interested in other book recommendations, check out this book list covering history, politics, and society.